The Roar Of The Mountain Lion

The following appears in the November issue of California Sportsman:

“My husband tells me you’re in sharks,” Ellen Brody declares to oceanographer Matt Hooper in the film Jaws. Let’s go ahead and say wildlife manager Jim Williams is in mountain lions and has studied and obsessed over these majestic predators in a career spanning multiple decades of research and two continents. And he hopes he and the next generation continue experiencing cougars in their natural settings.

“Big, wild cats worldwide are in trouble, threatened and endangered,” Williams writes in a new book about the phantom felines this former surfer from San Diego has grown to love and has vowed to preserve their legacy as one of the planet’s most remarkable species.

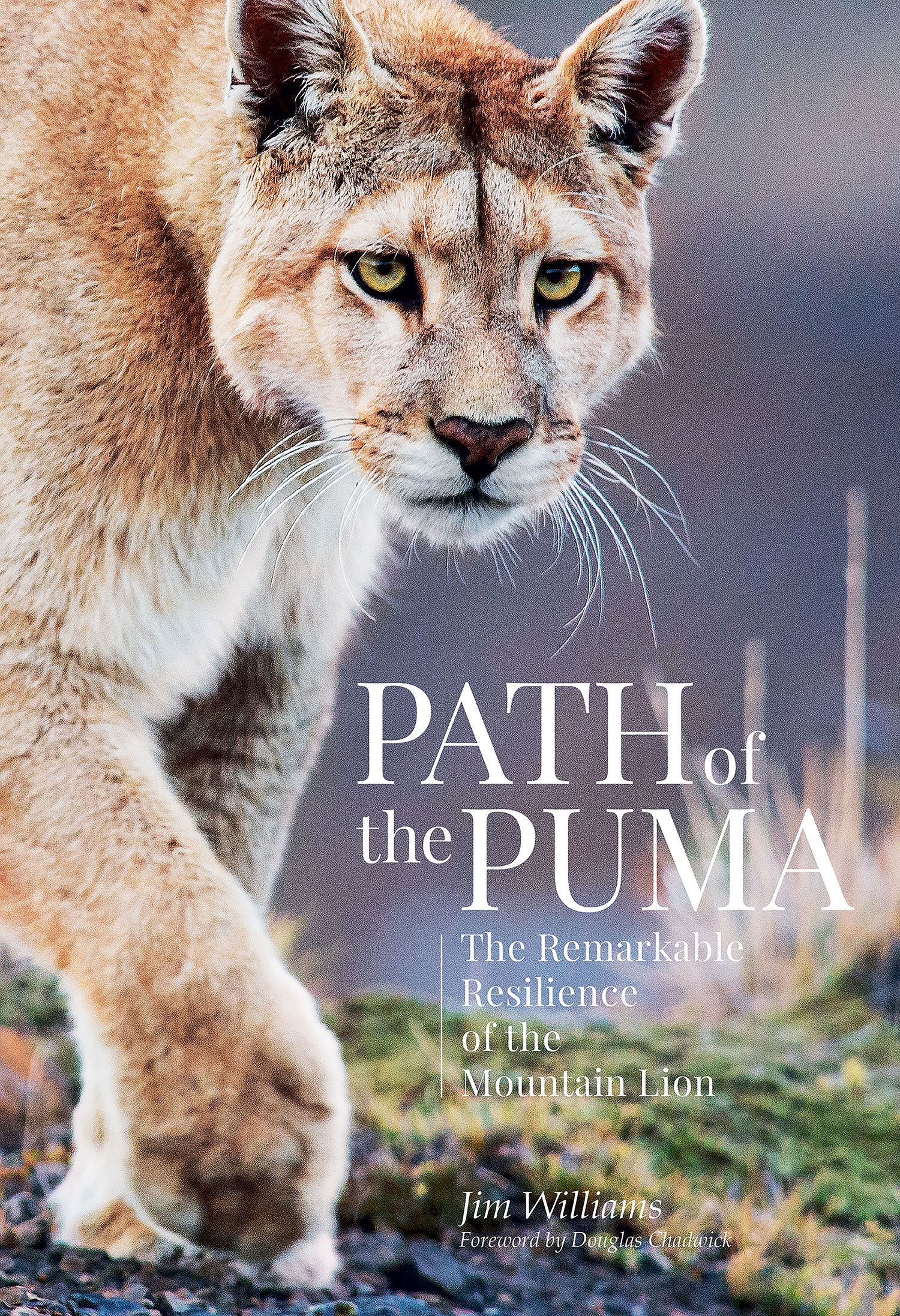

The following is excerpted from Path of the Puma: The Remarkable Resilience of the Mountain Lion (© 2018) by Jim Williams. Published by and reprinted with permission from Patagonia Books.

–Chris Cocoles

“In the process of natural selection, given a liberal allowance of time, it is the lion’s claw, the lion’s tooth and need, that has given the deer its beauty and speed and grace.” – Edward Abbey, The Journey Home

By Jim Williams

Not only did the Buckhorn Bar look like an authentic 1880s Western saloon, it often acted like one. One night during my first Christmas in town, the daughter of a well-known local rancher, home from college, was sitting at a nearby table with her friends.

Also in the bar were half a dozen loggers, tough thirsty men who’d been out by Smith Creek all week cutting trees by hand. Before long, a wobbly logger began hitting on the rancher’s daughter. That prompted her father’s workers to lay down their pool cues and drift over. I was about to advise the logger to move on when a ranch hand tapped him on the shoulder.

Three things happened, very quickly: the logger turned around; the rancher’s fist sent him reeling; and the bystanders immediately joined the fray. Amid the chaos, the logger got to his feet, jumped over the bar, and sprinted out the back door of the Buckhorn Bar to the Lazy B Hotel, three doors down Main Street. The crowd followed.

When the sheriff’s deputy arrived, the logger was poised like a fencer in front of his second-story room, waving and revving his chainsaw every time a ranch hand advanced. Finally, the deputy herded everyone but the logger back to the Buckhorn, where we could all return to a more refined, less combustible drunkenness and frivolity.

Welcome to Augusta, Montana, “the last original cow town in the West” – at least according to the Augusta Chamber of Commerce. With my arrival in 1989, the population swelled to 251. My job was to track big cats and to add to mountain lion science, but most folk here were more interested in how to keep their cattle safe from the hungry carnivores.

Founded in 1844 – back when Montana was still a territory – and named after the first child born there, Augusta is located 15 miles off the Rocky Mountain Front on a vast and windy grassy plain. Look east, and you see an ocean of American prairie, where massive herds of bison thundered not so long ago. Look west, and a tremendous mountain rampart soars straight up from the grassy flats, a stretch of alpine peaks known as the Rocky Mountain Front.

Those summits are some of the wildest country left in America, part of the rugged Bob Marshall Wilderness. Locals know it simply as ‘The Bob,’ a million pristine acres comprising the fifth-largest protected wilderness in the Lower 48, home to wolves and wolverines, bears and big cats. Its peaks crash into the prairie the same abrupt way its predators crash into the cattle herds.

Ironically, The Bob takes its name from a city slicker: Bob Marshall, born in New York City in 1901. He was a plant scientist, writer and prodigious walker, who logged countless miles through the unmapped country around the South Fork of the Flathead River. He cofounded The Wilderness Society, and campaigned to preserve places where people could travel for weeks without crossing a road. One year after his death in 1939, just such a wilderness in Montana was created in his honor.

Augusta was where I lived: The Bob and the Front were my office. It was a dream assignment – tracking mountain lions for my graduate thesis under the direction of none other than Dr. Picton. Author of the book Saga of the Sun and the definitive elk migration research in The Bob, Dr. Picton was one of Montana’s early wildlife biologists in this Sun River country. In fact, he was still known as Harold “Tall-in-the-Saddle” Picton by some of the locals.

Given his time in the field and depth of knowledge – and the fact that he’d trained many of the staff now working for the Montana Fish, Wildlife & Parks Department – in my world he held sway. When the time came for me to choose a master’s thesis project, Dr. Picton told me that although big cats had been studied in Yellowstone National Park and some other Western states, there was little information about them in The Bob and Rocky Mountain Front. I was excited to fill in some of those gaps.

In technical terms, the Sun River drainage is inhabited by a unique species array made up of a large numbers of both resident and migratory ungulates as well as large carnivores. In laymen terms, this country is a messy and migratory cycle of eat and be eaten. The ungulates – “meat with feet” as the writer Doug Chadwick calls them – include elk, white-tailed and mule deer, moose, pronghorn, bighorn sheep, and mountain goats. The primary carnivores are black and grizzly bears, wolves, and mountain lions; there are also lynx, coyotes, red fox, wolverines, and badgers.

From a wildlife biologist’s point of view, this broad “array of species” interacting across such a vast area – nearly three million acres when you include adjacent parks and wilderness areas – is unique in North America. With the exception of the extinction of wooly mammoths and the extirpation of the buffalo (which are slowly being returned to parts of the ecosystem), the rugged Rocky Mountain Front has changed very little since the Pleistocene ice retreated 10,000 years ago. This is old country, still intact, still wild.

My job here, with support from local biologists and state wildlife managers, was to spend a few years living among the mountain lions, tracking them to learn about their health, habits, and habitats. What did they eat, and when? How often did they kill? What did they kill? What kind of habitat did they prefer, during what time of year?

It’s big country, a geologic jumble of sawtooth ridges and deep river valleys, and to answer those questions I would travel it on foot, top to bottom, end to end. Today’s wildlife biologists can gather more data more quickly, employing GIS and satellite technology to track animals remotely from the comfort of the office. But I got my schooling in the analog era, when the only way to gather information was to literally live with the lions. Less data, to be sure, but also a different sort of data. More intimate. A satellite collar can transmit a location, tell you where a cat was and when. But unless you’re there, in the field, you miss the relationships that make nature work – the weather and the wind and the topography and the light that can explain why a cat was in a particular place at a particular time. What I lost in sample size, I gained in context.

Every time I have climbed a peak in The Bob, there were no signs of humanity in any direction. The entire area can be circled in a car a 380-mile drive – but not a single road crosses it. This was not going to be easy. Complicating my job was the fact that Dr. Picton didn’t believe in providing detailed instructions. As he told me many times over the course of the project – and as I was to learn for myself – failing repeatedly was part of the process.

MOUNTAIN LIONS ARE THE most effective and efficient large predators in the Americas. Period.

They are nature’s perfect stalk-and-ambush killer. What is astounding is that we, as a 21st century urban society, have allowed them to recover, not just across the West, but also, perhaps, in the East, where individual cats – mostly young males, dispersing from home – are even now pioneering new-old territories.

It’s a dramatic and unlikely turnaround, against the odds, from the near-eradication of cats in this country. For decades, states paid bounties for dead mountain lions, and unrestricted hunting was encouraged in an attempt to exterminate the predator. These policies had a predictably devastating effect on lion populations; when Lewis and Clark and David Thompson traveled west, “panthers” roamed the entirety of the Lower 48, Canada, Mexico, and Central and South America all the way to Patagonia.

But by the turn of the last century, the cats were virtually extinct east of the Mississippi – with the notable exception of the Florida panther, which survived only by retreating to the inhospitable swamps of the Everglades.

In the West, mountain lions found refuge in the wild, sweeping landscapes, but even there they were in trouble. My friend and mentor Maurice Hornocker, a pioneer in mountain lion and other wild cat research, estimates that by the early 1960s there were only 6,500 mountain lionsleft in the United States. It’s a best-guess number, but we do know that between 1936 and 1961 a staggering 3,219 bounties were paid in Washington state. Another 3,582 were paid in Oregon. And in California, 12,500 lions were killed between 1907 and 1972 for bounty or for sport. So depleted were cat numbers by mid-century that from 1932 to 1950, fewer than five mountain lions were taken each year in Montana.

Hornocker, setting out to study the great cats in the early 1960s, paid hunters $50 if they could tree a lion so that he could fit it with a radio collar for tracking. He ultimately collared an impressive fourteen cats, but studying them was another matter; by winter’s end, hunters had killed all but four. In 1964, Hornocker moved his research deep into the Idaho wilderness, launching a ten-year study that was the genesis of the lion science to come. It provided seminal information about all things cat – feeding habits, habitat, social structure, relationships with deer and elk, predation on livestock – and it opened eyes. Mountain lion predation, it turns out, was not having any serious effect on deer and elk herds, and neither were the cats affecting livestock in any significant manner. Hornocker’s data, in many ways, cleared the way for the end of bounties and unrestricted hunting, which in turn led to modern lion management and the tremendous and unlikely comeback we are witnessing today.

Cats are now thriving in their strongholds out West. More impressive still, they are slowly but surely rewilding our continent on the backs of deer and darkness, moving across the Midwest and southern Canada, on their way to New England. They are tracking ancient river-bottom routes, following prey down the Missouri, the Milk, the Saskatchewan, the long east-west rivers that are pumping lions from the Rocky Mountain Front to the Black Hills and beyond.

Anywhere there is enough human tolerance and prey, the big cats are reclaiming old ground. Minnesota’s dairy country. Ohio’s corn country. The farmlands of Pennsylvania, Virginia, New York. All of this is potential home range for tomorrow’s cat communities. Wildlife managers have successfully built up tremendous herds of white-tailed deer across America, for the benefit of hunters, and that prey base is driving the remarkable recovery of lions. It’s astonishing, really, considering that we are in the age of extinction for large predators in the Americas – and given our long history of eliminating any animal that can harm us, or, more accurately, our livestock.

SO HOW IS THIS happening? Why the mountain lion? And why is the mountain lion the only large cat on planet Earth that is increasing both in numbers and distribution?

It’s not just the deer. It’s the way we think about the wild. A radical change swept North America during the 1970s, an environmental ethos driven by the science of ecology – the science of the connections between the parts, and not simply the parts themselves. Ecology taught us the intricate relationships at play in the natural world, the “web of life” that includes everything from bacteria and photosynthetic green plants to insects to deer and elk and wolves. Most important, for mountain lions, ecology established that our native large predators also play an important role in these natural systems. Every one of the parts is needed if the ecosystem is to function naturally. Predators aren’t villains. They are indispensable.

I was a young man when the Endangered Species Act passed into law in 1973, and I still remember the beautiful National Wildlife Federation posters featuring a black-footed ferret, a wolf, and, of course, a resting mountain lion. These were the very beginnings of nationwide tolerance for predators, and of a drive toward natural and intact ecological systems throughout North America. It was a time of people awakening to the role carnivores played in ecosystems.

At the same time – thanks to groundbreaking 1960s field research by Maurice Hornocker in the wilderness mountains of Idaho – we learned that the lions weren’t, in fact, eating us out of business. His studies proved absolutely that mountain lions are dependent on healthy deer and elk herds. Contrary to the popular opinion at local coffee shops, the cats were not reducing the big-game hunter’s prized quarry. Instead, they were part of a system evolved to keep herds strong.

It’s difficult to overstate the importance of this science, as many of the cat hunters who once participated in mountain lion bounty systems began to realize that lions were more valuable alive – that they could enjoy their trained hounds while pursuing and photographing the big cats all winter long, if the carnivores were not eliminated. Those hound handlers carried heavy political clout in the rural western states. More than science and data, state wildlife commissions at the time listened to the hound handlers.

Before long, hound handlers began showing up side by side with university-trained wildlife biologists, demanding that mountain lions be made protected game animals, not bountied predators – and by the early 1970s that’s exactly what happened. State wildlife agencies eliminated bounties, and shifted 180 degrees to conservation and management.

The ripples spread through wild nature almost immediately. With new rules came a ban on the poison-laced baits that had been used to kill cats, but that also killed any other critters unlucky enough to sniff them out. One side effect was that wolverines, bobcats, martens, badgers, and countless other species were suddenly “protected” under the new rules for lion conservation. It was a foundation on which whole ecosystems could be rebuilt, and it helped drive the wild that would be necessary for mountain lion expansion nationwide. We made room for the lion, tolerated the lion, and wild nature did the rest, filling in the gaps with a complicated dance of predators and prey. And through it all, America barely noticed.

People died of domestic dog bites, bee stings, drownings and falls, and auto accidents. The rare encounter with a wild animal remains a statistical fluke. Humans are not part of the big cats’ “prey image,” and as long as we have strong deer numbers the lions mostly leave our pets and livestock alone. The cats, in essence, were invisible.

We live as fairly peaceful neighbors because we cannot see them. If we knew they were there, we might have second thoughts, but mountain lions make their living in the shadows, at dawn and dusk, and often can be quite nocturnal. We see only what they leave behind—telltale tracks and deer bones, a scatter of whitetail fur, prints in fresh snow.

The big cats have evolved for secrecy, to protect themselves and their kills from other predators – from bears, and especially from wolves – and also to enable their ambush hunting style. Not only do the lions move in darkness, and in heavy cover, but they do so on softly padded paws that are covered in thick hair to soundproof their approach. Even the claws retract to quiet each step. They’ve evolved to be almost scentless, a protection against wolves that, in today’s world, allows them to slip silently though neighborhood woodlots without triggering the alarm of barking dogs. They’re largely solitary, the better to go unnoticed, and they certainly don’t announce their presence by baying at the moon. In other words, they really are the ghosts of the Rockies. The adaptations that allowed them to survive and hunt in a world of wolves, deer, and elk are proving to be the key to their expansion in a world of dogs and humans.

I WAS SENT TO Augusta to study mountain lions, but over my career what I’ve learned about the big cats has taught me as much about Homo sapiens as it has about Puma concolor. We fear the threat we can see.

Tigers and African lions are far more visible, and we’ve nearly wiped them out. But we don’t see the mountain lion. What does that say about us, that the only big cat in the world that is expanding is the one we can’t see? CS

Editor’s note: For more information, check out pathofthepuma.com and order the book at patagonia.com/shop/books or on other sites such as Amazon and Barnes and Noble.

Q&A WITH AUTHOR JIM WILLIAMS

Editor Chris Cocoles caught up with Path of the Puma author Jim Williams, who talked about his California roots and his love for the big cats he’s spent his career studying on multiple continents.

Chris Cocoles Congratulations on an awesome book, Jim. What was your inspiration for writing this?

Jim Williams I have always enjoyed sharing stories about wild things and wild places. I really wanted to tell some of the adventure stories about some truly magical animals and landscapes – the Crown of the Continent in Montana and Patagonia (Argentina and Chile). These special places are home to some amazing colorful species at both ends of the world. And I have always wanted to write a book. I love books!

CC You were born in Iowa but spent your teen years in San Diego. What was the California lifestyle like for you?

JW Growing up surfing on longboards made by the legendary Skip Frye, saltwater fishing from those same surfboards and free diving the reefs around Pacific Beach in San Diego changed my life. When I finally donned a mask and peeked beneath the waves that my friends and I enjoyed so much I was amazed at the diversity of life underwater. I knew then I wanted a marine biology degree and I ended up at San Diego State University. The smell and taste of the ocean on the morning breeze from an old beach cruiser bike, the sweet scent of orange trees in bloom and the bright red colors of hibiscus flowers will forever be etched in my mind. The Pacific Ocean was my wild place and I will always love California for that.

CC In the book you write about paddling out on your board in the Pacific to fish for sea bass and rockfish. What kind of memories do you have of those days?

JW There is no better-tasting fish than freshly caught marine fish. We used to use our teeth to clench the soft part of the rod while we paddled with our arms out to the local kelp beds near Tourmaline Surfing Park (La Jolla). We would use a weedless rubber Scampi lures to jig in and around the towering stands of brown-colored kelp. The brightly colored rockfish and sea bass tasted the best.

My surfing buddies and I also enjoyed using Hawaiian slings to spear halibut and corbina. They all were quite tasty as well, especially cooked in tinfoil over an open fire on the beach. I never had much money, so these fish were always quite a treat. Angling brings all of us closer to nature and inspires us to protect clean water.

CC Where did your fascination for mountain lions begin?

JW My parents took me to the movie theater to watch Charlie the Lonesome Cougar (1967) when I was a child. I knew immediately that I wanted to learn more about this big brown cat that lived in some pretty wild mountains. After completing my first marine biology degree I wanted a change, so I hung an old shark jaw on my rearview mirror and loaded everything else I owned into an old red Jeep Scrambler and drove out west. I ended up at Montana State University in Bozeman and jumped on the opportunity to study mountain lions for a graduate degree. I have never looked back.

CC You’ve done a lot of your work about mountain lions in Montana, but do you have some perspective about the cats’ population in California and what the future might hold for the species in the Golden State?

JW Unfortunately, we as humans are the most influential force on the planet. Right or wrong, it’s up to us if we decide that we want to share our landscape with large carnivores that can potentially eat our pets, livestock or even pose a safety risk to humans. For mountain lions, these types of conflicts are not the norm as long as we still have big wild spaces with plenty of native prey species. In California that typically means deer.

I think that maintaining genetically connected populations of big cats with places that they can safely cross your busy highways and interstate freeways is perhaps your most difficult challenge. The good news is that building crossing underpasses or overpasses works. We have them in places throughout Montana. The bad news is that they are often quite expensive to build. How much is having the mountain lion on our wild landscapes worth? For me there is no question. It’s our responsibility as a society to conserve these amazing animals and the wild places they live.

CC I used to live in Thousand Oaks in Southern California and there is a plan in place to (someday) create the Liberty Canyon Wildlife Crossing over the Ventura Freeway (U.S. 101) in Agoura Hills. It looks like a fascinating though complicated idea, so how much can that and similar projects offer indigenous California critters a lifeline with so much human intervention in their way?

JW Crossings under highways – if designed correctly – will benefit many native species. Some (conservationists) like tunnels versus large underpass structures – depending on species behavior. They are expensive, but they are worth it.

CC You penned a great chapter about suburban populations sharing space with predators such as mountain lions. I grew up in San Mateo County in the Bay Area, where there have been many sightings and even attacks in suburban communities. How difficult is it for lions to coexist with human beings with so many people around in the Bay Area and Southern California?

JW There is no question that mountain lions are the most effective predator in the Americas. They can also pose a safety risk to us humans at times. Human-lion conflicts are actually quite rare, but when they happen it’s of course tragic for both family and friends. (Editor’s note: Two people were killed by cougars in Washington and Oregon this year, the first fatal attacks in either state in nearly a century and in the historical record, respectively.)

It’s entirely appropriate if we have to remove an individual problem mountain lion to maintain tolerance for the entire population. It’s all about the entire population and healthy habitats versus the individual problem cat. If there is enough wild space with deer there will be lions in California; it’s as simple as that. When we break up wild spaces and build neighborhoods next to or in deer habitat we are going to need to learn how to live with mountain lions. It will always be a challenge.

I think that information and education for all residents in the urban wildland interface is your best hope. I have found throughout my career that most people truly care about all wildlife but they need good information to minimize their impact on wildlife populations. Bottom line: support your local land trusts. Your best hope is to work with willing landowners to secure conservation easements or outright acquisitions to permanently protect the wild places you have left. Time is not on your side in California.

CC Some of my favorite sections of the book are your research on pumas in South America’s Patagonia (parts of Argentina and Chile). How much of an adventure has that been for you in such a rugged but beautiful corner of the world?

JW I had heard about the landscapes; I had heard about the good food and wine; I had heard about the wildlife. But in the end I fell in love with the people of Patagonia. They are a passionate bunch that are very proud of their unique part of the world. The biologists I worked with are doing so much with so little. I also thought that Montana was big and wild until I first traveled to Patagonia. The mountains are immense, the ice caps of the Andes are spectacular and the windy steppe in Argentina is endless. On top of that the wild animals represent this crazy mix of pink flamingos flying by glaciated peaks, wild camels, ostrich-like rheas, penguins, chinchilla-like viscachas, and more. For a Montana wildlife biologist, Patagonia represents an inspiring array of bizarre species just begging to be studied more.

CC Is there something that I would be shocked to know about mountain lions that I probably should know?

JW Yes. They in a sense limit their own numbers behaviorally. The resident adult densities on the landscape are quite similar from the southern tip of South America to Montana. You hear many rumors about too many cats, but their populations can be quite consistent if we tolerate them on the landscape. A cat is a cat is a cat.

CC And for you, an expert on these remarkable big cats, is there something that you don’t know about mountain lion behavior that you’re trying to figure out still?

JW Of course, especially in Central and South America, where they have been studied less. Interactions with other species is still fascinating. With new technologies we will always have new windows into their secretive lives. I love that.

In the end, however, I think we will always need to work with local communities and provide accurate information and assistance with conflicts – both urban and rural – to make sure wildlife conservation is durable. CS