The Highs And Lows Of An Iconic NorCal River

The following appears in the September issue of California Sportsman:

By Chris Cocoles

Photos By Jason Hartwick/A River’s Last Chance

The rivers around Shane Anderson’s boyhood and current home of Olympia, Washington, are well known for either their beauty or magnificent runs of salmon and steelhead, or both.

But it was time studying at Humboldt State University and fishing the North Coast’s rivers that had a far more profound impact, none more than the Eel.

“It’s a river that changed my life. I’m indebted to it,” he admits.

So much so that Anderson, a fisheries biologist major turned filmmaker, paid homage to the Eel in his documentary, A River’s Last Chance, an historic biography of an important Northern California river and the people who depend on and/or adore it. The story plays out like a Greek tragedy but with a – presumably, conservationists hope – happy ending for the watershed that once was the lifeblood of Native tribes, commercial and sport fishers, loggers and pot growers.

The river and its fauna have taken more punches than a tomato can boxer, whether the knockdowns were via man-made or natural causes.

“It was always an extremely productive and abundant place prior to the arrival of the colonial world; just so productive on its own before we killed it,” says Anderson, who provides a lot of details about the ups and downs of the Eel’s salmonid populations, which seemed doomed to extinction.

“And the fact that they’ve come back gives me hope, because if they come back from all that, we’ve turned the corner and they should be fine.”

But what a roller coaster ride it’s been on this iconic stretch of water.

“I see the salmon as this symbol of how we need to do it. If we can keep the salmon healthy and the habitat healthy, then we’re doing alright for ourselves.”

–Eric Stockwell, Eel River Recovery Project and Loleta Eric’s Guide Service owner, in A River’s Last Chance

Anderson’s fishing experiences on the Trinity River regularly in the early 2000s eventually drew him to go back to school at Humboldt State, where he majored in fisheries biology to fulfill his fascination with the science side of his love of steelhead and salmon fishing. He’d also spent time in Los Angeles in the film production industry. Combining these two passions seemed like a no-brainer.

“I kind of had the epiphany while going back to school there that if I could combine my background with film production and science that maybe I could be more effective in educating and inspiring people about how to save these places, rather than just being a scientist,” says Anderson, once a competitive downhill skier.

In 2012, he started his own production company, North Fork Studios (northforkstudios.net). His first feature documentary, 2014’s Wild Reverence, focused on the struggles of steelhead runs around his Pacific Northwest home base. But it was fishing on the Eel that kickstarted something altogether different.

He recalled the first time fishing the South Fork along the famed Avenue of the Giants for steelhead. His first wild Chinook gobbled a Blue Fox in an area known as the 12th Street Pool.

“I had no idea the place existed,” Anderson says. “It was one of those special places, but at the same time for many years my only experience on the Eel was either along the Avenue of the Giants or the lower river. I had no idea how vast that watershed really was until I started this project.”

“I started exploring the Middle Fork and the North Fork and up to the dams. And then you’re like, ‘Whoa! This place is huge’.”

“The Eel River is part of our life; it is our bloodline … the heart that pumps into our land. It was home to us. Without that river we wouldn’t be who we are today.”

–Ted Hernandez, chairman, Wiyot Tribe

As Anderson says in his A River’s Last Chance opening-scene narration, “Some places along the river are like going back in time 10,000 years.”

The 196-mile-long mainstem of the Eel – it got its name when 1840s explorers exchanging Pacific lampreys for cookware with Wiyot fishermen misidentified the aquatic creatures as eels – empties into the Pacific about 20 miles south of Eureka in Humboldt County. And each and every mile, not to mention the South and Middle Forks, runs with history.

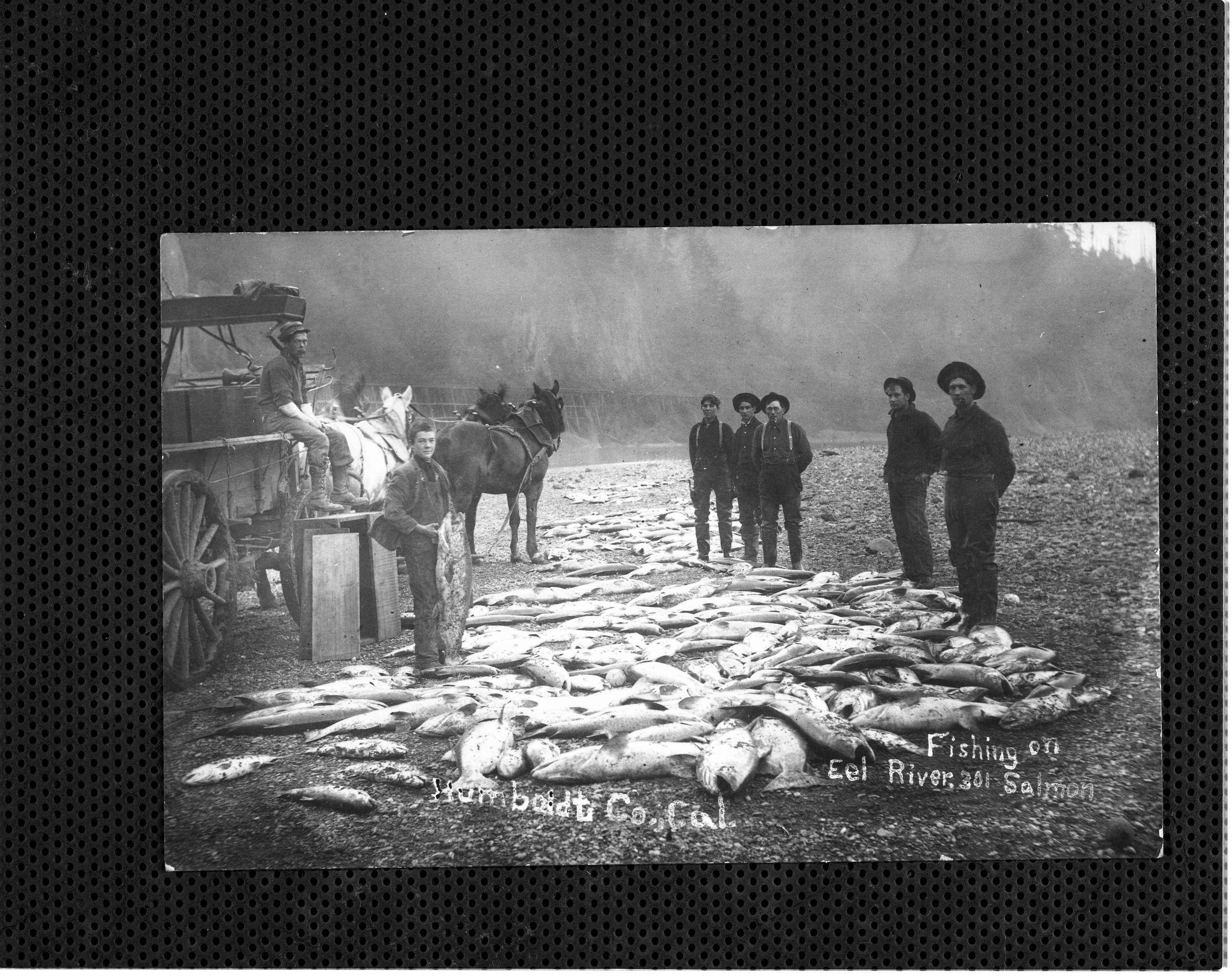

Sixty-five Native American tribes once called this region home, with the Eel drainage serving as the lifeblood of their subsistence lifestyle. In the 1850s, the river’s annual salmon runs – estimated to be as many as a million fish – attracted commercial fishermen and canneries, turning what is now sparsely populated wilderness into a boomtown. It didn’t take long for sport anglers to also flock to the Eel – Anderson heard stories of the Van Duzen River, one of the Eel’s major tributaries, once being a steelhead fishing destination for the rich and famous through remote fly-in lodges – and overfishing of both the commercial and recreational harvest made for a predictable decline. Two dam projects, Cape Horn Dam in 1908 and the Potter Valley Project’s Scott Dam in 1922, have been polarizing issues.

Commercial fishing on the Eel was eventually banned, though the damage had been done, and by the turn of the 20th century, the tall trees that graced the region created another lucrative industry, timber. Still, old timers who appeared in the film remembered the 1930s, 1940s and 1950s as still being world-class for salmon fishing.

“I remember thinking this deliberately: There are so many goddamn silver salmon in these coastal rivers of California, we can’t hurt them,” angler and artist Russell Chatham says in the film. “You could go down there with a fishing rod and kill every one that you caught. And it wouldn’t mean anything.”

“I read accounts of people having 30-fish days for steelhead in the middle of summer,” Anderson says.

You can see how this trend was going to eventually fizzle out.

“The Eel seems to be a river of ups and downs, or better yet of boom and bust. It is a river that was compromised by settlers taking advantage of its resources (salmon, timber, and water), pretty much the three most important things to a healthy river system,” says Jason Hartwick, the associate producer and cinematographer for A River’s Last Chance and owner of Arcata-based Steelhead on the Spey Guide Service (707-382-1655; steelheadonthespey.wordpress.

“Salmon canneries damn near wiped out the salmon by the early 1900s, then logging went into full effect for the next 100 years, to where now all that we are left with is about 4 percent of old-growth redwood forests, water diversion through the PVP project, and now the ‘green rush’ (marijuana harvesting). We don’t seem to learn from our past mistakes and just continue going down the same road of destruction.”

“One of the most giving species on Earth. They swim out to the ocean, get fat, come back and give all that marine nutrient to the inland environment, to people. Free, healthy, beautiful, self-sustaining source of protein and food. If that’s not a beautiful gift from nature, I don’t know what it is.”

–Mike Wier, Cal Trout, filmmaker

Four years after massive flooding in 1964, the Eel’s mainstem and South Fork salmon and steelhead runs came in at 9 percent of where they were in the plentiful 1940s.

“Even when Chatham and Jim Adams from the movie started fishing in the early 1950s, they were still having amazing fishing days, and that was after it had already been depleted,” Anderson says.

Then Governor Ronald Reagan’s late 1969 audible spared the river from being dammed again by the Dos Rios Dam project, and there were moments of brilliant salmon runs in the 1980s. But the excess had taken its toll, the area’s timber industry went bust and the salmon were designated an endangered species.

Then in 2010, a UC Davis study concluded the Eel’s coho, Chinook and steelhead were “on a trajectory towards extinction.” As if defiantly refusing to go down, the Eel’s 2012 run of Chinook was surprisingly and wonderfully massive. Anderson fished for steelhead that year and couldn’t believe what he was experiencing.

“I was there fishing every day and I’m catching more fish down here than I ever have on the Olympic Peninsula. And I was fly fishing and gear fishing. On the fly I was averaging five fish a day, which is unheard of. And that lasted for like five years. And I was like, ‘Holy sh*t.’ And nobody was down there.”

But soon, the water diversion used from cultivating marijuana – often illegally – became the new timber boom in Humboldt County and adjacent areas where cannabis is plentiful. As if that wasn’t enough to all but finish off the Eel, one of the state’s most devastating droughts in recent memory wreaked havoc in the mid-2010s.

But the California Department of Fish and Wildlife and other agencies accelerated the crusade to eliminate illegal marijuana harvesting, offering another lifeline of sorts for the Eel.

“The marijuana thing is a little frightening, but that’s falling apart as fast as it booms. It’s completely changing up there as we speak,” Anderson says. “It won’t be long until most of the green rushers are gone. Fish and Game has really cracked down.”

“Man has done a really good job of trying to hurt this river and hurt the fish, but these things are just so strong and persevered through everything.”

–Kenny Priest, fishing guide and outdoor writer

The drought took its toll on the Eel just like other rivers throughout California. Yet in 2016 as wetter winters finally began to restore some order in the ecosystem, back came the fish. And in the Eel River, it’s wild salmon and steelhead only, as hatchery fish are no longer released in the watershed. The Eel has become one of the West Coast’s most successful wild salmon and steelhead fisheries.

Anderson hopes his film will continue to share the message that the Eel’s future is bright and not bleak.

“I think a lot of people still have lost hope. A lot of local fishermen don’t even understand that even the good years a few years ago, I don’t think they either remember a much more abundant time or they don’t really have a baseline on how things are on the rest of the West Coast,” he says. “Maybe it’s because it’s closed to harvest; I don’t know. We definitely met people along the way who think it’s still dead, and I can assure you that it’s coming back.”

Hartwick agrees, but also offered a warning.

“The future of the Eel depends on the people who work, live and care about it. The river has great potential to recover salmonids, but everyone has to work together,” he says. “That being said, the only way we will see a healthier Eel River and increasing fish numbers is with more cold, clean water.”

Hartwick sees the Potter Valley Project and diverting more water from its Scott Dam onto the Eel as a critical talking point to sustaining the watershed for the long term. But that issue is ongoing as a group of conservationists vie for an opportunity to purchase the project from PG&E and ensure that more of that valuable cold water is diverted to the river.

Political issues aside, the Eel’s story of excess, decline and rebirth of its wild fish is told beautifully in A River’s Last Chance. Anderson, who despite his deep roots in the Pacific Northwest, has an emotional attachment to the Eel, is filled with a feeling many have lacked or been leery about embracing over the last half-century: hope.

“I think we’ll get to over 100,000 Chinook. If you look at it there’s no harvest; there are no hatcheries; the timber practices have dramatically changed. There’s a really good chance that (Potter Valley Project’s dam is) coming out, especially now that PG&E has said they’re going to auction it off. And at the very minimum, even if the dam stays there will be better management of it,” he says.

“And there all these habitat projects in the estuary being redone and dug out. CalTrout just pulled out a barrier in (Mendocino County’s Woodman Creek) and they’re doing it right now. It’s going to access another 14 miles (of spawning water). So we’re going to keep building with this restoration economy and we’re already seeing a lot of the spawning tributaries heal from a lot of the last wave of the timber boom in the mid-’90s. So I’m just seeing recovery all over the place … I don’t see another boom/bust in the future. I don’t even know what that would be. How can you not be optimistic? I think it’s the first time in the Eel’s history and the salmon’s history that they actually have people on their side.” CS

Editor’s note: You can purchase a DVD of A River’s Last Chance and its companion book, Seasons Of The Eel, at northforkstudios.net/shop-1. The film will also be shown at select film festivals this fall, including two in Northern California. Check northforkstudios.net/

WHAT THE EEL MEANS TO A LOCAL

My friend Meg and I share roots in Northern California, though I didn’t meet her until years later (and her husband Sean and I actually grew up about 25 miles from each other, unbeknownst to us after we all met).

But while I lived in the suburban sprawl of the Bay Area, Meg’s ’hood had access to redwood trees; the closest landmark to our house was a 7-Eleven.

(Not that I’m complaining; my friends and I had too much fun going to Oakland A’s baseball games, which we could drive to in 25 minutes or get to on BART in at most an hour. I just did that same trip to the Oakland Coliseum in August!)

When Meg and I talked about her wanting to see a screening of a documentary about the Eel River, A River’s Last Chance, I told her I was planning a story on it, and she said she wanted to relive her childhood memories of this special waterway.

If you knew Meg, you’d be inspired by her passion – about social justice issues, beer (she’s spent most of her career working in production for craft breweries), baseball. So I’m not surprised she has such a spiritual connection with the Eel having grown up in the Eureka area.

“My sisters and I grew up with summer day trips to Women’s Federation Grove, on the South Fork of the Eel River,” she said. “There was an absolutely perfect swimming hole – complete with rock jumping and log walking. Across the river and down the road is Albee Creek Campgound. This is my peaceful, happy place.”

Meg said watching A River’s Last Chance “brought me to tears,” and as I saw it and then chatted with director Shane Anderson, I could understand why the locals would feel emotional heartache but also hope about the Eel’s many setbacks and glorious recoveries from overfishing, timber industry stripdowns, floods, drought and now marijuana cultivation. Meg recalled when Maxaam Inc. took over local timber company Pacific Lumber in the 1980s.

“I had many friends whose parents worked for Pacific Lumber. I experienced and witnessed the change in harvesting practices. Towards the end, Maaxam was able to convince people that their business practices weren’t the cause for people losing their jobs; the environmentalists were,” she said. “It was an incredibly sad and scary time. Decades later, after I moved to Seattle, my home is still trying to recover. My youngest sister works for the Bureau of Reclamation. A few years ago she sent me a video; it showed the first time in recorded history that the Eel River had run dry. It broke my heart.”

Like Meg, we all are attracted to a hard-luck story, and it’s hard not to fall in love with the gritty Eel, given that despite all the adversity its salmon and steelhead runs are exclusively wild with no hatchery stocks, a rarity on the West Coast.

“If I catch a hatchery fish it’s fun and all good, but I don’t get that same excitement of ‘Wow!’ In this river these things survived the gauntlet and these fish were the survival of the fittest,” Anderson told me. “These were the chosen ones that were able to make this odyssey and not only survive the river, but one of the hardest parts of their lives are those first two years. I just have a reverence for the animal and they sure as hell battle harder.”

A River’s Last Chance might just be our last chance to experience something that extraordinary. Here’s Meg, who lived through some of the Eel’s most tumultuous times, with the last word.

“I am so thankful for Shane taking the time to document the history of the small place I call home. It’s an incredibly special place that not many people are lucky enough to experience. I can only hope that we truly learn from our past behavior and right the many wrongs of our past.” -CC