Process-Based Restoration Resuscitates California Creeks

The following is courtesy of the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service, Pacific Southwest Region;

For millions of years, nature has been designing and building river and wetland habitats, which are some of the most diverse and productive systems on Earth. These habitats, also known as fluvial systems, benefit society by providing important?habitat?for wildlife, supplying drinking water and?irrigation?for crops, delivering electricity through?hydropower and more. However, they are imperiled due to human alterations resulting in habitat loss, degradation and fragmentation. Overtime, there’s been a growing interest in “Process-based restoration,” whereby the practitioner addresses underlying causes of degradation so the stream can rebuild and restore the wildlife habitat on its own.

To reverse some of the damage, process-based restoration focuses on restoring natural process, for instance, reconnecting streams to floodplains or mimicking beaver presence. While restoring natural process shows promise, many restoration efforts still rely heavily on civil-engineered design requiring large quantities of rock, fossil fuels and heavy equipment to construct stream channels and stabilize banks. These efforts may be counterproductive as they protect streams from the very processes, such as channel migration, needed for a healthy ecosystem.

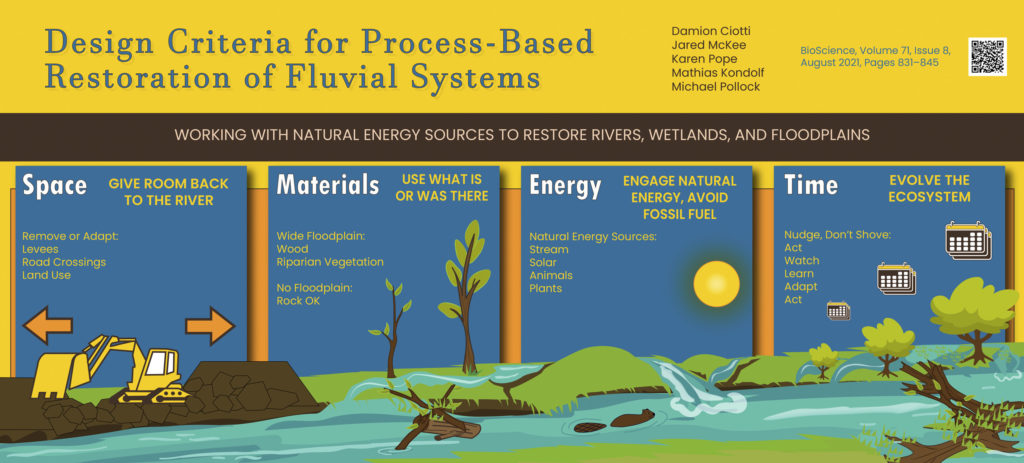

A team of scientists evaluated projects and reviewed over 30 years of scientific literature and found successful process-based restoration had four common components of space, energy, materials and time. These projects provided more space and connectivity for the stream to move, capitalized on natural energy and materials such as flooding and wood from the project site, and they were adaptively managed over time. They then applied these components as design criteria for project implementation and came back with groundbreaking findings.

“The results were rapid and with higher levels of biodiversity at a lower cost-per-acre than standard stream construction,” said Damion Ciotti, San Francisco Bay Coastal Program coordinator, U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service. “With a little training, practitioners can easily integrate these approaches with ongoing stream restoration efforts.”

Take a deeper dive into this new research…