Fishing For Freedom At Manzanar

The following appears in the April issue of California Sportsman:

“I will cleanse my soul, in the mountain stream. Face down my fears, and dare to dream. And for that moment of quiet dignity, I will feel what’s it like to be free.”

–Lyrics from “To Be Free” (by Harold Payne), performed in the film The Manzanar Fishing Club

By Chris Cocoles

There’s a scene in Cory Shiozaki’s film about Eastern Sierra trout fishing that could come straight out of an REI commercial or chamber of commerce promotional video.

Two men, armed with fishing rods, are climbing up a plateau with a backdrop of bright sunlight dipping below the tall peaks of the mountains that surround this trout angler’s paradise. It’s a beautiful sight that screams peaceful serenity.

But then you remember that what you’re watching is far more than just a trout fishing movie. The voiceover during the scene is Dene Nui, daughter of James Motoike, a resident of Block 15 in a United States’ version of a Second World War concentration camp. Motoike hadn’t committed a crime, mind you, except that between 1941 and 1945 Motoike and other Californians of Japanese descent were considered security threats while America was at war with the Empire of Japan.

Manzanar, located in the dusty high desert of the Owens Valley between the Eastern Sierra and Inyo Mountains, was the most well-known of the internment camps and would hold roughly 120,000 persons of Japanese descent from shortly after Pearl Harbor through more than four years of fighting until Japan’s formal surrender on Sept. 2, 1945. About 10,000 were interred here at any one time.

Motoike was one of thousands of Japanese-Americans and immigrants from Japan sent to camps like Manzanar, smack dab in the middle of some of the state’s best trout fishing waters. He was one of a few incarcerated men, women and children who found brief moments of freedom at Manzanar while fishing just outside the camp’s fences of barbed wire and towers with armed guards.

“My father’s biggest stories – or his biggest fish stories – were always about sneaking out of Manzanar,” Nui said in The Manzanar Fishing Club, a 2012 documentary.

Director Cory Shiozaki is a Southern California resident and avid trout angler whose own parents were interred in two other camps among several spread throughout the Western states during the war.

“He would always say, ‘We would sneak out under their noses,’” Nui added. “And being able to run away essentially for a day was something that embodied his personality and his way of communicating his unhappiness. And that the only freedom that he ever had was in fishing.”

And for an angler who for years as a licensed Eastern Sierra trout guide with a personal connection to the story of these oppressed American citizens treated as enemies of their own country, Shiozaki, who studied film at Cal State Long Beach, found a project he would embrace.

“At some point in my life, I did want to tell that story that my parents didn’t tell me about incarceration,” he says. “All along, this idea of what had happened with the executive order, I became very obsessed with the idea that this is a story that needs to be told.”

YES, IF YOU HAD Japanese ancestry, lived on the West Coast after the Japanese attack on Pearl Harbor and were subject to Executive Order 9066, signed by President Franklin D. Roosevelt on Feb. 19, 1942, your life was turned upside down.

After the Dec. 7, 1941 Imperial Japanese Navy attack that devastated Battleship Row and the United States Pacific Fleet – save for its aircraft carriers, which were at sea and perhaps saved America from destruction – President Roosevelt delivered his famous “A date which will live in infamy” speech. A little more than two months later, FDR’s executive order would ultimately send Shiozaki’s parents to camps in Idaho and Utah, respectively.

With widespread panic that the West Coast was the next target as Japan set its sights on conquering Southeast Asia, Japanese-Americans became an enemy within their own country compared to the enemy who resided on the other side of the Pacific. Especially out West, they were even thought of as bigger threats than those of German and Italian heritage as fighting would escalate in the European theater.

“Even though they were American citizens they were reclassified as enemy aliens,” Shiozaki says. “So having that placed on them as ‘Hey, you’re an enemy alien,’ it created a lot of difficult (feelings).”

Propaganda and fear are both omnipresent in wartime. Leaflets warned that those of Japanese descent were a threat to America. The film showed a “California Jap Hunting License” patch – “OPEN SEASON-NO LIMIT” – with a caricature of a hunter aiming his weapon.

In other words, having Japanese blood during that time brought new meaning to being an American. In a propaganda video that appears in the film, the United States Government spun the camps as being a comfortable alternate home away from home for internees. (“The Japanese in America are finding Uncle Sam a loyal master – despite the war,” the video’s narrator shockingly said.)

But in the early years of the war Manzanar felt like the maximum security prison it resembled as internees stayed in Army barracks with cots, a stove, a light bulb hanging from the ceiling, and not much else.

Shiozaki’s film – his close childhood friend Richard Imamura wrote the script for the documentary – shows many of the anglers being held at gunpoint when they attempted to leave the camp for a day of fishing in one of several nearby creeks. But the act of defiance and feeling of freedom trumped the risks involved.

“Sometimes people ask, ‘Why would somebody leave the camp to go fishing?’ ‘Why would they crawl out through the barbed wire, under the tower and potentially risk their lives to go fishing?’” Manzanar National Historic Site chief interpretive ranger Alisa Lynch said in the film.

“And I think the answer has a lot more to do with just catching a fish or being a sportsman. I think it has to do with the human spirit and the desire to be free. And to do something that you love when you’ve been taken away from everything that you know.”

“That feeling of freedom and doing the trout fishing outside of the camp, it was really a satisfying feeling,” said Archie Miyatake (Block 20, Barrack 12, Apartment 4), who as a young boy at Manzanar managed to slip through the barbed wire to fish with his older cousin. “Because you feel like you can put one over on the government.”

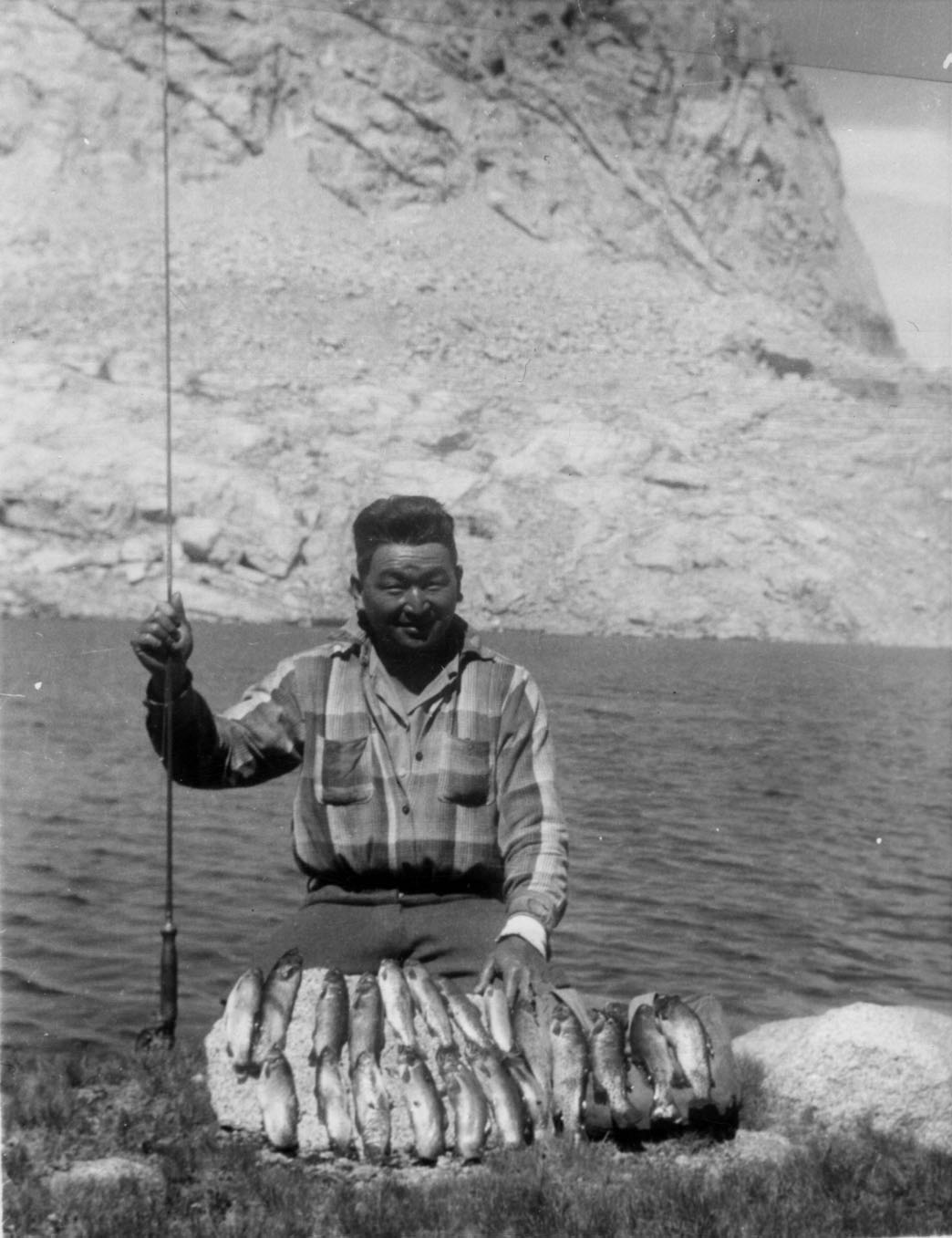

Archie’s father Toyo, a renowned Los Angeles photographer, managed to use a makeshift camera to capture images of life at the camp. Those photographs included a shot of another camp internee, a 50-something-year-old gentleman known back then as “Ishikawa the Fisherman.”

In the iconic photo that would eventually become the poster for The Manzanar Fishing Club, Heihachi Ishikawa (Block 20, Barrack 14, Apartment 4) is holding a stringer of golden trout caught in waters a long hike outside the camp. When he saw that grainy photo, Shiozaki was fascinated and wanted to learn more.

“Since cameras were contraband and not permitted, technically (Miyatake) did not have a camera. He had a lens and film holders. While he was in camp, he had some carpenters build him a box camera out of wood and took pictures,” Shiozaki says. “And eventually, one of the photographs during the time he stayed at Manzanar was this guy who was a neighbor of his holding a stringer of golden trout. ‘How the heck did this guy catch golden trout if he was incarcerated?’”

Shiozaki had to find out.

A TRUE BABY BOOMER, Cory Shiozaki was born in 1949. He is a third-generation Japanese-American, known as a sansei. Cory’s mom Leah grew up in the Bay Area and dad Ron was from just outside Portland, Oregon. After the Pearl Harbor attack sent the U.S. into war with Japan, Cory’s parents were sent to camps far from home, Dad to Minidoka, about 20 miles from Twin Falls, Idaho, and Mom to Topaz, in western Utah.

The Shiozaki family restarted their life with what little they had left (at the end of the war, all interned at the camps were given $125 and a train ticket, which Shiozaki reminds was the same restitution federal prisoners received upon their release from prison).

Ron and Leah Shiozaki ran a small grocery store on Chicago’s North Side. Five years after Cory was born, the elder Shiozaki got a phone call from a friend and was convinced to move to Gardena, a city in the South Bay area near Los Angeles and home to one of the state’s largest populations of Japanese-American residents. Ron Shiozaki then ran a successful clothing store business after relocating to Southern California.

But it wasn’t until he was in college that Shiozaki knew what his parents endured a few years before he was born. By the late 1960s, a time when many of Shiozaki’s age took up a cause, he found one when he learned what happened to his parents and other West Coast residents with a Japanese heritage during World War II.

“The Vietnam War was happening and I was draft-eligible. In fact, I think my draft number was 158 and it went up to 253 or something like that. So I was about to be drafted,” he says. “At the same time, I learned about the incarceration of Japanese-Americans, which I’d never known about. So I confronted my dad and asked him why he never talked about it.”

“I was very, very adamant about this because the social injustices (of the time). The civil rights movement was starting to get momentum and (there were) anti-war demonstrations. And I was so upset about what had happened with this executive order. I told my dad that in protest I was going to go to Canada. He got very angry and I said, ‘Why are you not condoning my belief in this protest of what they’re doing in this genocide war against Asian people, considering what happened to you guys?’”

But Mr. Shiozaki was just as defiant, telling Cory that if he fled for Canada he’d disown his son.

“His reply was, ‘Right or wrong, this is the only country I know.’ And I was taken aback by that,” Shiozaki says. “He wouldn’t support my choice to want to protest in this manner. But out of respect for my father, I honored his wish and ended up serving six years in the Army.”

But while he served his country – even one that in his mind turned its back on the previous generation of Japanese-Americans – Shiozaki was obsessed with knowing what really happened in the internment camps.

Starting in 1969 and every April since, interned survivors and their families have participated in the Manzanar Pilgrimage at the camp – run now by the National Park Service – to honor those who were sent there.

In his senior year of college, Shiozaki created a short film about Manzanar, picking the brain of Sue Kunitomi Embrey, the founder of the Manzanar Committee that started the pilgrimage in 1969. He went to his first pilgrimage at Manzanar in 1972, as determined as ever to unlock new secrets about the experience of American citizens locked up in detention centers and camps.

“Of course, there were basically just ruins. There wasn’t much that the government left to show that this type of thing had happened. They wanted this to be a lost memory,” says Shiozaki, who aptly named his production company From Barbed Wire to Barbed Hooks LLC.

“This happened and the government didn’t want to bring it up anymore. And neither did a lot of the Japanese-Americans who were incarcerated for a variety of reasons. Partially because there was a lot of shame and guilt associated with being incarcerated. It was just bad memories. Everyone wanted to forget about this and not relive it.”

But he pressed his parents to open up to him, mostly just to provide them a semblance of healing.

FISHING IS OBVIOUSLY THE centerpiece of The Manzanar Fishing Club. Both Ron and Cory shared a love for fishing. One of Cory’s favorite stories from his dad – Ron passed away in 2014 at 98 years old – was from his Oregon days as a young man.

“He graduated from the University of Washington in 1939. Before that he was living near Westport, Oregon, where his family was from. One time he went fishing on the Columbia River and caught a couple salmon,” Cory Shiozaki says. “And a game warden came up on him and said, ‘Nice fish. Let me see your license.’ My dad was pretty quick-witted and said, ‘Oh, I’m Native American and don’t need a fishing license.’ And the warden walked away.”

Cory really got into trout fishing in the 1990s, and while his dad knew more about catching salmon than trout, Cory was skilled enough to guide Eastern Sierra trips while being a seasonal resident of Bishop in the mid- to late 2000s.

It was also about that time that he spotted that photo of the Manzanar fisherman and his stringer of trout. After spending 37 years with the International Cinematographers Guild and, among other projects, was part of the camera crew on the Academy Award-winning film Dances With Wolves (1990), Shiozaki began to tirelessly research Manzanar’s fishing legacy.

“I started with just the intrigue of one photograph and started asking the park ranger staff at Manzanar if they had heard of anybody else doing this. And at the time, when the interpretive center opened they were actually pursuing taking oral histories of surviving people from Manzanar,” Shiozaki says.

“And when they would go out and do these oral histories, I asked them before they got a hold of these people, would they mind asking preliminary questions whether or not any had connection or activity with Manzanar families that were going fishing while they were incarcerated. And the ones that they did stumble on – maybe a half dozen – I would tag along with them during the interview for these oral histories.”

Two internees that struck a chord with Shiozaki were Ken Miyamoto, who knew how epic the trout fishing was around the camp he was being sent to, so he brought along his tackle like hooks, leaders and sinkers. And Shiozaki also sat in on an interview with Jiro Matsuyama, who took a job with a crew supervising the reservoir adjacent to the Manzanar camp.

“They gave him a vehicle, so he had a lot more accessibility to go in and out of the camps. What he would do is order his equipment from Sears and Roebuck and used to go out fishing and would take his friends out,” Shiozaki says of Matsuyama. “But in the beginning, he didn’t want to get caught, so he declined all these offers and pretended to be ignorant. ‘No, I don’t know anything about fishing.’ Later on he was able to assist people leaving the camp and sneaking out toward the reservoir.”

He had something to work with now. With an assist from his friend Imamura, paying homage to those anglers who made the best of some of the worst times of their lives was taking shape.

THERE ARE SEVERAL COMPELLING moments The Manzanar Fishing Club recalls during that challenging time (and the few internees who did talk about their fishing experience are just a handful of thousands who lived through Manzanar and the other camps with remarkable tales of their own).

The anglers who sneaked out sometimes crawled under the cloak of darkness to avoid being spotted. They made makeshift rods out of sticks and rakes, used bent paper clips to create hooks and found everything from worms to kneaded balls of rice for bait.

The film recreates the infamous Manzanar Riot on Dec. 6, 1942 – coincidentally around the one-year anniversary of Pearl Harbor – that led to a shootout with guards and left two internees dead. But there was also a human element to the ordeal for the Japanese-Americans, including a heartwarming story of an MP who gave one young boy, Mas Okui (Block 27, Barrack 12, Apartment 1), droplines to fish with in a brown paper sack. Okui and his friends had unsuccessfully tried to catch trout, first with their bare hands and then safety pins at the end of balls of string.

“That was an act of kindness,” Okui said in the movie.

One of Shiozaki’s favorite stories from his research was one he had to cut from the film. Near the end of the war, about the time the U.S. had dropped the atomic bombs on Hiroshima and Nagasaki and the war seemed destined to end, a group of internees wanted to make one last long hike to fish a remote high-elevation lake.

One of the members of the party was a middle-aged man who wasn’t in the best of shape but was an artist who decided to stay behind and paint while his friends fished. But an unexpected snowstorm blanketed the mountains and the fishermen huddled in a cave. They never found their friend.

“They made maybe three attempts with search parties to look for him and couldn’t find him. And about a month later there were two hikers from Independence (who wanted to climb Mount Williamson),” Shiozaki says. “And when they were hiking they noticed a wooden stick protruding from the rocks and felt that it was an anomaly because they were above the tree line and there’s no wood up there. And they went over to take a look at what that was, and what happened was that was the guy’s fishing pole next to the decaying remains of the fisherman. They just buried him up there.”

MANZANAR SHUT DOWN FOR good on Nov. 21, 1945 and the government mostly tore down the camp structures, leaving a small trace of what went on that’s preserved today at Manzanar National Historic Site.

But with the Manzanar Pilgrimage returning every last weekend in April – ironically coinciding with the statewide trout opener – those who lived through the war from inside and outside the barbed wire fences will always remember what happened there.

And for Shiozaki, The Manzanar Fishing Club also has its own tribute on both sides of Highway 395 about 1½ miles north and 1¼ miles south of the camp.

“We feel that we have a certain responsibility to continue to tell the story and the narrative. And what we’ve done going on three years now is we’re volunteers and have Manzanar Fishing Club Adopt-a-Highway signs up near Manzanar,” he says.

“And twice a year in the spring and the fall we go up there and pick up trash off the highway as part of the remembrance of Manzanar. We are always reminded that this is something that we want others to know. We take pride in that we have the opportunity to bring awareness to the site by this highway sign.”

One of those clean-up weekends is scheduled for May 17, and a day later Shiozaki and Imamura will host a walking tour of the camp and a special screening of the film.

His parents were well into their 90s when Shiozaki was working on the film and securing enough funds to complete the project, which spanned 6½ years. Ron and Leah, who had both been slowed by dementia, got to see rough cuts and snippets of the film before Cory finished the final version.

“Whenever they saw images in the film of the barracks and everything, it struck a chord with them and they did make comments. ‘Oh wow! That’s camp,’” Shiozaki says. “Like so many in that generation, it really created a very important thing in their lives. There were all kinds of mixed emotions about it.”

Shiozaki’s parents had a typical way to get past whatever bitter feelings they must have had during the war and what they and other Japanese Americans were subjected to as their country fought in the Pacific theater. Leah, who is suffering from Alzheimer’s, is now 101, almost 75 years after she faced the indignity of camps like Manzanar.

Perhaps fishing was a way for The Manzanar Fishing Club participants to lift a collective middle finger to their plight and injustices. Shiozaki hopes many, like his parents, moved on the best they could.

“There’s an expression that’s the mantra of all these Japanese people in the different camps. The saying that you’ll hear from other Japanese people that’s very common, it’s called shikata ga nai, which literally means ‘It can’t be helped.’ In modern times, shikata ga nai means ‘Sh*t happens,’” Shiozaki says. “But in the Japanese culture it’s something they use to maintain themselves. Hey, it happened; it’s water under the bridge. There’s another saying called ganebette. That means ‘Just hang on and keep it together.’”

“Those things, which I find for myself, are some of the values that were passed down through generations about how to live your life. One of the things that I learned through my parents and my ancestors is the fact that when you have adversity and things that happen when you have no way of changing, it’s a form of acceptance. There’s no sense of being bitter and angry about something that was beyond your control. How do you benefit from staying angry about this? How do you continue to be bitter about something that you have no control over? That kind of philosophy kind of helped me in my adult life. You just kind of do the best you can.” CS

Editor’s note: To order a DVD of The Manzanar Fishing Club, go to fearnotrout.com and like at facebook.com/

Sidebar

A HOMETOWN CONNECTION TO INTERNMENT CAMPS

My dad was 9 years old on Dec. 7, 1941, when the Imperial Japanese Navy’s task force attacked the U.S. Pacific Fleet at Pearl Harbor. But for my dad’s parents and brothers and those living in San Francisco, Dec. 8 was just as, if not more, scary than the day before.

“We were all convinced San Francisco was going to be attacked next,” he once told me.

At the time, it probably was justified to have that fear. But the fact is that fear turned to paranoia, and West Coast Japanese-Americans were unfairly subjected to incarceration in dreary concentration camps like Manzanar.

Cory Shiozaki, who directed the 2012 documentary The Manzanar Fishing Club (page 13) had his own personal connection to the persecution of people of Japanese descent. And when he said his mom Leah, whose family lived in the Bay Area, was first sent to the Tanforan Detention Center, it literally hit close to home.

Tanforan, now a shopping center, is located in my hometown of San Bruno. It was once a horse racing track that legendary colt Seabiscuit once trained at. But the facility, which burned to the ground in a 1964 fire, was also utilized as an assembly center early in World War II for internees to stay at on a temporary basis before being transferred to permanent camps.

“They quartered these people in horse stables with the stench of manure. You couldn’t eliminate that smell,” Cory Shiozaki told me about what his mom and her family endured at Tanforan before they were transferred to a camp in Utah. “They whitewashed it; they mucked up the stalls, but there was still a lingering stench of horse manure.”

Today, in front of the main entrance at Tanforan, a mall I spent many a summer day at watching movies at the theater, eating at the food court and generally hanging out with my friends and family, there’s a sizable statue of Seabiscuit. There’s also a more modest plaque reminding mall patrons that the ground here was used for more than thoroughbred racing and shopping.

I was glad my dad had a chance to watch The Manzanar Fishing Club with me, and I too was honored to write about Shiozaki’s cinematic gift to those brave internees, who found some peace through fishing at a time when both the best and worst of America was on display. -Chris Cocoles