Angel Of The Battlefield: A Navy Doctor And Sportsman’s Journey

The following appears in the May issue of California Sportsman:

When he was entering his fourth and final year of medical school, Donnelly Wilkes was excited about his future as a doctor and an ensuing career in the United States Navy.

But when terrorists hijacked four planes on Sept. 11, 2001, causing thousands of deaths and sent a reeling nation into mourning, Wilkes’ euphoria turned to uncertainty and fury.

“The United States has been attacked! I’m astonished at the sight of the burning buildings, bewildered at how such a thing could happen to us. A feeling of dread comes over me as I stare at sobbing, terrified New Yorkers running through ashen streets,” Wilkes writes in his memoir. “My sadness quickly

turns to anger, and all I can think of is ‘Oh God, what can we do now, what happens next?’”

Wilkes grew up in Placerville, which is about 50 miles east of Sacramento, in a family with plenty of military ties and that also had a love for hunting and the outdoors (see our interview in the following pages). Wilkes did his undergraduate work at Orange County’s UC Irvine and attended medical school at Tulane University’s School of Medicine in New Orleans on a full Navy scholarship.

Dr. Wilkes graduated from Tulane and embarked on his service as a lieutenant commander in the Navy, which

would eventually take him on seven years of active duty, including two combat tours in Iraq as a field doctor in 2004 and 2008. He would be awarded the Navy Commendation Medal with Valor for his actions in the Battle of Fallujah in April 2004.

These days, Dr. Wilkes runs a clinic in Southern California and still enjoys outdoor adventures in his home state and throughout the West. His book details the highs and lows of his time in combat, where he and colleagues worked tirelessly to save the lives of soldiers wounded in combat during the Iraq War.

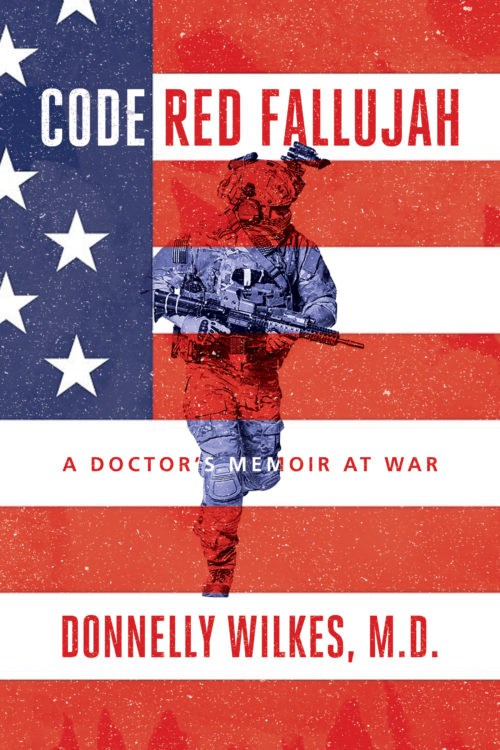

The following is excerpted from Code Red Fallujah: A Doctor’s Memoir at War by Dr. Donnelly Wilkes and published by Post Hill Press/Simon & Schuster.

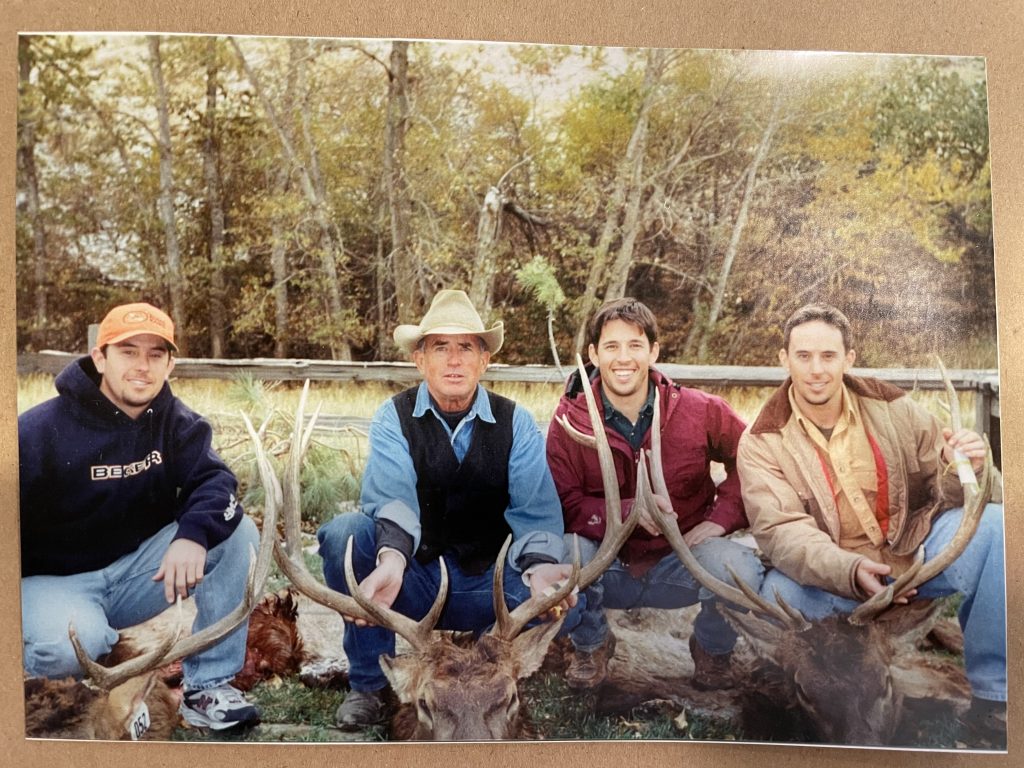

During one convoy ride to an Iraqi police station , Wilkes (far right with his siblings and father, Mike), put in a dip of tobacco, which was “something I reserved for hunting trips and ‘male bonding’ with my brothers; Iraq brought back the indulgence.” (DR. DONNELLY WILKES)

By Dr. Donnelly Wilkes

Throughout the deployment our battalion worked closely with the Iraqi police, training them and conducting joint missions during offensive operations. This is in preparation for when Iraqis will eventually take over security enforcement of their cities and ultimately their country.

It is an extremely time-consuming, frustrating and difficult task for the Marines. There are only a few Iraqis with meaningful experience in law enforcement, and those who have the training use unorthodox techniques, tactics, and procedures. They are ill equipped and underpaid, making retention extremely precarious. All these problems are inherited by the Marines. Throw in cultural and language barriers, and it becomes a slow and endless dance of two-steps-forward, one-step-back progress. Despite this, our men work diligently with the Iraqis towards their sovereignty, committing money, uniforms, weapons, and hours of blood and sweat to the cause. Corruption and thievery are rampant among the Iraqi ranks, and when caught it is important to call out and punish these individuals to deter this behavior.

On June 7 [2004], I attended a staff meeting outlining a plan to detain and prosecute five criminal individuals discovered among the Iraqi police. Our battalion commander plans to arrest and parade them in front of fellow Iraqi police members, sending a message that corruption will not be tolerated. The plan is to take a team of Marines to the Iraqi police station in Al-Garma during what should be a routine payday for the Iraqis. I will join the mission with five corpsmen to perform brief medical exams for each Iraqi officer as a gesture of good will and as a diversion tactic.

After the corrupt members are paid and complete their medical exam, they will be placed in handcuffs and escorted in front of all other policemen, sending a message that corruption will be dealt with seriously. The remaining Iraqi police will be paid promptly and thanked for their service. This mission is named “Operation Silent Switch.”

OUR BATTALION LAWYER IS Capt. Jamie McCall. Among many nontraditional duties you might expect of a lawyer, his job is to pay the Iraqi police. For the Al-Garma mission, he will take thousands of dollars in cash to pay each member of the Iraqi police.

After learning about the medical role in the operation, I suspect we will be working closely together. Jamie and I first met in Okinawa before leaving for Iraq, and over the past couple months we became fast friends. He attended law school at Penn and shortly after joined the Marine Corps.

I saw a lot of myself in him; his passion for life and commitment to duty as a Marine Corps officer inspired me. We bonded quickly, in part because we both chose professions sometimes perceived by society as those of opportunity, yet we found ourselves amidst war, executing our vocations in a capacity we never truly imagined.

During deployment, we killed time in the gym tent or jogging around the base, discussing our lives as young men, and dreaming of the life awaiting us upon return to the states. In the evenings we played Ping-Pong, watched movies on a laptop, or hunkered down with [Lt.] Cormac [O’Connor] and the chaplain for a competitive game of spades or Scrabble.

Mid-deployment, Jamie developed an infected cyst in an unfortunate region requiring minor surgery. It was this event that propelled our friendship closer than either of us ever intended! In a second medical mishap, Jamie headbutted an air conditioning unit; he laughed it off with grace as I closed his scalp with seven sutures.

Hunting with his dad and brothers has always been a big part of Wilkes’ life. “My father taught me the camaraderie found in hunting and the love of nature,” he says. (DR. DONNELLY WILKES)

IT’S SATURDAY, WE’RE 174 days into the deployment, and Operation Silent Switch is a go. In the back of my head, I’m telling myself, “Don’t do anything stupid; you’re on the home stretch.” Capt. McCall walks in the BAS [battalion aid station] with a friendly greeting and reminder of the fun and adventure we will have spending the day in Al-Garma. I assemble a crew of five corpsmen, and we pack a few medical bags for basic exams, mostly for show as a diversion tactic.

Jamie and I hop in the back of a Humvee, and our convoy heads out at 8 a.m. It’s already getting hot, at least 90 degrees, and I suspect we’re in for a long day of travel. Per protocol, we stop just outside the gate, exit the vehicles, and load our weapons. Facing away from the Humvee, I insert a clip into my 9mm pistol, pull back and release the slide, chambering one round. I flick the safety up and I’m ready to go. The convoy lurches forward together, turning west onto the main highway for a short distance, then exiting on an unmarked dirt road I only half-recognize from a previous convoy. Our routes constantly change, using back roads and making our own paths to avoid predictability, ambushes, and IED attacks.

I tuck a bit of chewing tobacco in my lower lip for the road trip and peer out the window at the barren desert terrain that distracts me from our destination. Before Iraq, this habit was something I reserved for hunting trips and “male bonding” with my brothers; Iraq brought back the indulgence, since nearly every other marine carries chewing tobacco in his front pocket. We bump along the dusty roads, passing muddy, sewage-filled canals. Three weeks ago, one of our Marines drowned in this canal. While swimming across to span an electrical conduit, his feet became entangled in weeds and rescue attempts failed.

On dirt roads, we travel through miles of crops and fields inhabited by the occasional farmer. Small farm towns punctuate the long stretches, most of them poorly constructed clay huts or rock structures, with dirt-caked walls. Children run in the streets, waving to us as we thunder by. I marvel at their acclimation to the war all around them and the fragility of their daily life. Marines wave back, throwing soccer balls and other trinkets brought just for this occasion.

We arrive in Al-Garma before noon, linking up with Bravo Company Marines stationed across from the Iraqi police station. They live in a large open bay structure with an aluminum metal roof and block wall perimeter. I enter the building headquarters and see to my left a few folding tables with laptop computers, maps, and field telephones. The remaining open bay is filled with a maze of sandbags, field gear, ammunition, and green mesh cots with silver aluminum legs. The latrine is just outside the main entrance, consisting of a dirt hole and boxes. Overheated from the journey, we unload our gear, wrestle off our helmets and flak jackets, and grab some water. Jamie and I sit side by side in metal folding chairs, waiting to hear when to depart to the police station. We open magazines to pass the time. Jamie picks up a copy of Field and Stream; pointing at a large fish, he fondly describes a prior catch, and I share in the spirit with my plans for an elk hunt in October with my dad and brothers.

KA, KA, KA-BOOM, BOOM, BOOM! We’re violently jerked back to reality when multiple mortars crush the ground outside. I lurch forward to reach for my helmet at my feet. As I strap it to my chin, three more rounds pummel the earth, closer than the last. Boom, Boom! I search frantically for my flak jacket as others race for cover, but it’s not where I set it down.

Bodies rush past me on all sides. Frustrated, I scramble to crouch against the wall as the impacts continue. They cease a few moments later, but I remain still, heart pumping and lungs heaving with adrenaline. After a minute, I tentatively stand up to look around. No one seems to be hurt, and there are no direct hits on the building. I look over at Jamie. We both sigh with the same air of exasperation, as if to say, “Same story, different day.”

I walk over and jokingly thank him for inviting me to such a memorable outing.

TWENTY MINUTES LATER, WE load up the vehicles with our gear. We head across the street to the Iraqi police station. Once there, we enter a building where the Marines have gathered a couple hundred policemen. Once lined up, the herding of bodies begins.

I’m positioned in a small dirty back room with two corpsmen and an interpreter. As each Iraqi comes in, the interpreter asks if he has any medical problems or takes any medications. My corpsmen document the answers, then check his blood pressure and pulse while I listen to his heart and lungs. The first five men are the policemen suspected of corruption, and as they exit the room, they are arrested and placed in handcuffs.

Despite the meaningless nature of the remaining medical exams, we continue the same process for every single Iraqi as a gesture of goodwill and an effort to support them. Most of them do not speak any English, but their faces and thankful expressions are understood. It is tedious, dirty, and hot and I’m anxious to head back to Camp Mercury upon conclusion.

Our unit musters outside the compound, facing a formation of Iraqi police officers. The corrupt officers are escorted in front of the other Iraqis as a commander explains why these men have been arrested and that this fate will follow anyone participating in this kind of behavior.

I meet Capt. McCall outside the compound, where we gather our gear and saunter back to the Humvees, sharing frustrations and triumphs alike. Despite the mortar attack, it’s a successful and motivating operation. We load up the convoy and head for home. Our armored convoy drives, bounces, and bumps along highways, back roads, and no roads; some of it is familiar to me, while much is different from the way we came.

I catch glimpses of abstract shapes, shacks, and shadows in the distance – a dead animal, an abandoned hut, a goat herder – all of it feeling suspended in time. The success of the day and journey back to the base have me feeling a pull towards home so powerful it feels as if my return is in the near future. The convoy rumbles on, leaving massive dust clouds in its trail.

As we pass the outer limits of our base, two stout Marines coated in white powder dust wave us through. I feel the tension in my head decompress and the nerves in my chest unwind; we are at home base once again. CS

Editor’s note: For more information and to order the book, go to simonandschuster.com/books/Code-Red-Fallujah/Donnelly- Wilkes-M-D/9781642938029.

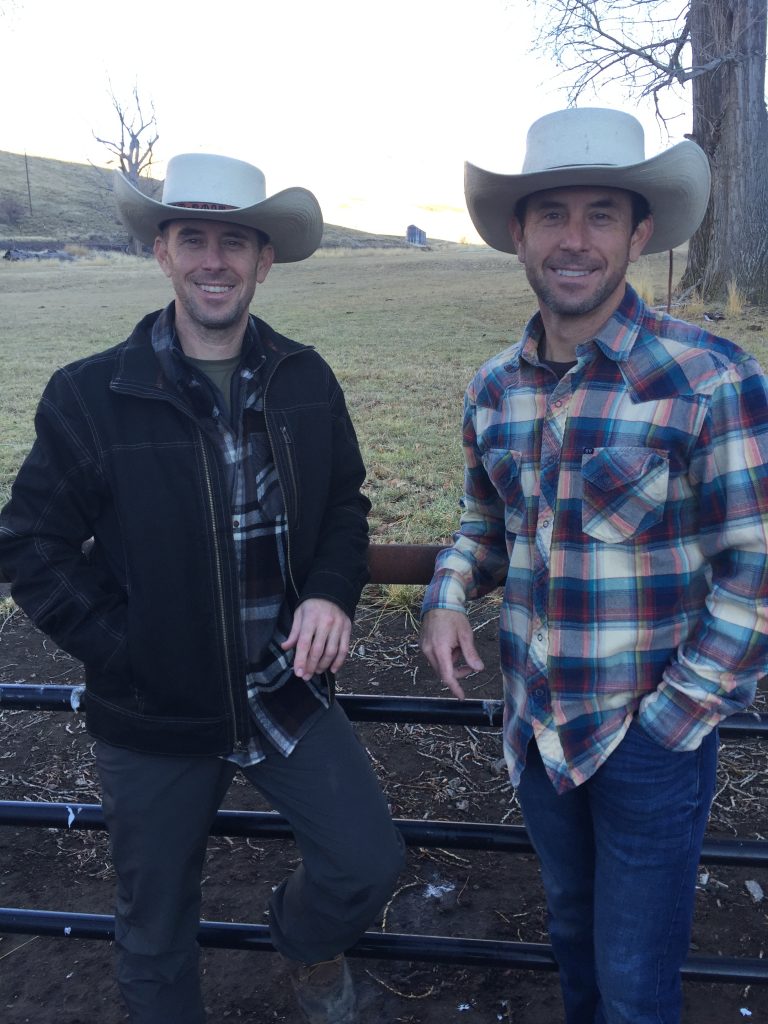

Growing up in Placerville as part of an outdoors-loving family that also had military bloodlines, Donnelly Wilkes had a pretty good idea what he wanted to do. He became a Navy doctor and in his new book, Code Red Fallujah: A Doctor’s Memoir at War, he chronicles his experiences in Iraq. (DR. DONNELLY WILKES)

Sidebar: Q&A WITH DR. DONNELLY WILKES

We chatted with Dr. Donnelly Wilkes, who served multiple deployments in Iraq with the U.S. Navy, about his experiences in combat (including a desperate attempt to save a wounded serviceman, Lt. Jackson, which appears in Wilkes’ book), his love for the outdoors while he grew up near Sacramento, and his Thousand Oaks-based Summit Health Group, of which he’s president and medical director.

Chris Cocoles Congratulations on a really compelling book. What inspired you to pursue this project?

Dr. Donnelly Wilkes After returning from my deployment and as the Iraq War dragged on, I realized what an important event the battle of Fallujah had been, and how it had changed me. There were only a handful of physicians as close to combat as we were in Fallujah. Moreover, the Battle of Fallujah proved itself to be the premier and most violent event of the entire 10-year Iraq War.

Three years after Fallujah, I found myself in desert boots once again, heading back to Iraq for another deployment. Memories and emotions from Fallujah were stirred. I needed something to help get me through another deployment, and I felt a calling to tell my story from Fallujah. It was then that Code Red Fallujah came to life. My writing helped me harness the positives from my combat deployments, release emotional strain, and evolve as a physician.

CC And considering some of the horrors of war you witnessed in Iraq, was writing this book a bit cathartic for you?

DW Yes, it was. As my second deployment commenced, it stirred up emotions from the Battle of Fallujah. My writing helped me put my thoughts on paper and work through some tough memories from Fallujah. It also helped me express the importance of my faith – and its ability to help us endure.

CC You have a lot of military connections in your family – your grandfather fought in World War II and Korea and only an injury prevented your father from enlisting during Vietnam – so was pursuing a career in the Navy something you always thought about along with going to medical school?

DW The culture in my family has always been one of patriotism. America is our beloved home team, and whether up or down I learned to support and root for our nation’s endeavors. Service to our country was frequently celebrated at family gatherings. I knew at a young age I would follow suit in some capacity but wasn’t sure how. I let my passion for education and adventure drive this ship, so when the Navy offered me a full scholarship for medical school, that ship set sail.

CC How much did the Sept. 11 attacks impact you as a young man in the armed forces?

DW When the [World Trade Center’s] Twin Towers came down, I was in my fourth and final year of medical school – on the cusp of fulfilling my dreams as a medical doctor. That day, I sensed my career as a Naval officer would be much different. The tide had turned, and I felt an even stronger pull towards active duty. I felt edgy about what it might mean to go into harm’s way but pumped up to be a part of the best fighting force in the world. By this time, I had attend- ed officer training school in Newport, Rhode Island, and I was ready to don the uniform and jump in the ring.

CC I was so moved by your experience trying to save the life of Lt. Jackson. You write about how much that moment affected you spiritually. Looking back, how much did that shape who you are now?

DW This event truly altered my evolution as a physician, Naval officer and Christian man forever. That night was a turning point in my deployment. I was really struggling with the intensity of combat trauma and incoming mortars and rockets we were receiving at our field aid station. Jackson’s death put me over the edge, and I felt myself bursting at the seams. The spiritual reckoning I write about is what turned the battle in my favor, and I have never forgotten that lesson. In my personal and professional life, I have drawn on the strength I gained over and over again. I have the good Lord’s strength on my side, and with this, I cannot fail.

The trials of life still wound me, but they don’t inflict as much pain and I bounce back quicker. I have more empathy for my patients, and I see their struggles and rough sides through a softer lens. My temper has softened, and my ability to find time for the simple love of life has evolved. I am a better doctor, husband and American because of that night.

CC You grew up around Sacramento [Placerville]. That’s such a great outdoors mecca. Is that where your love of hunting evolved?

DW Yes, I learned to hunt in the oak tree- lined foothills of our home in El Dorado County. We started with pellet guns hunting rabbits and quail right in our backyard. My father taught me the camaraderie found in hunting and the love of nature. He taught me to clean our kills and we always ate what we hunted. We moved on to hunting deer outside Placerville in the Sierra Nevada, and then finally to bigger hunts out of state.

CC Can you share a California hunting memory?

DW This story comes straight from my father, Mike Wilkes:

“Donnelly and (brother) Riley were 8 and 9 years old and excited for our annual deer hunt. It would be the three of us and another hunter friend of mine. Typically, my friends left their kids home but not me. Our destination was halfway between Placerville and Lake Tahoe, 20 miles north of Highway 50 in the Sierra Nevada. We drove in on dirt roads as far as we could go. Then all of us loaded up with backpacks and hiked over 4 miles to make our camp.”

“In those days, money was tight, and I did not bring good equipment for myself or the boys. It started to lightly snow at dinner time on the first night. Initially, we thought it was great, but before long the light snow turned to rain as we were still cooking on the campfire.”

“Eventually, we had to retreat into our tents. Thus, it began the most miserable night I have ever had. Our tent was a joke – not only did the rain seep right through the top, but it also ran like a river down the seams of the floor, soaking every- thing in its path. Riley was the only one who had an air mattress and stayed dry in his sleeping bag. Donnelly and I were doomed as the streams below the tent floor blossomed and soaked our sleeping bags. Donnelly was freezing and climbed into my bag. Huddling skin to skin was all I could do to keep him warm. I stayed awake the entire night, hating myself for getting us into such a horrible situation. Thankfully, Riley slept soundly on the air mattress!”

“Before dawn, I escaped from our water-drenched tomb, packing all our gear in the dark. At first light, we were ready to hike out of the snow-crusted forest. We made it down the mountain in record time, bringing a safe end to our adventure. I can say without a doubt it was the worst night I have ever spent, and I vowed to never skimp on gear or go hunting unprepared ever again!”

CC My dad was in the Navy and he’d talk to me a lot about the brotherhood of those you serve with. Did you feel that even more about those you not only worked with but those wounded warriors you treated?

DW Yes, when you have a wounded man or woman under your care, you feel the ultimate responsibility to care for and protect this person who has been wounded. Throw in combat in the background, and this event or moment becomes crystallized in your memory. I remember the details of their wounds and the vulnerability in their eyes. Some persevered gloriously, while others succumbed to the ultimate fate. Each of them had a deep and lasting impact on me.

CC Are we doing enough for our veterans after they come back from combat?

DW During and since my service the care for our veterans has come a long way. But like [actor and veterans’ activist] Gary Sinise says, “We can always do a little more.” As a physician and a patient, I have personally provided and received medical care in our VA system and can attest to the vast improvements over the last 20 years. Now that we have made great strides in the access and delivery of medical care for our veterans, we can continue to refine and improve all services offered.

I want to personally bring attention to the following mental health services:

The National Center for PTSD, which has free consultation for any provider treating veterans for PTSD or related issues. PTSD Coach App: an evidence-based app with information for family, friends, or patients on symptoms, screening tools, links to support, and treatment options.

CC You’re a dad now. What would it mean to you for your kids to follow in your footsteps of pursuing a career in medicine or the military, or both?

DW I am an all-girl daddy, and we frequently talk about Dad’s adventures in New Orleans, the Navy and beyond. Admittedly, sometimes my stories may get a bit “inflated.” It gets harder and harder to impress them as they grow!

The Wilkes household frequently celebrates the stars and stripes, posting our flagpole together for honorary holidays. With all the opportunities blossoming today more than ever for women in medicine and the military, I would support any choice they made to follow in my footsteps.

CC It sounds like you’ve done a lot of hunting in different areas of the country. Is there a hunt that’s on your bucket list?

DW I would love to go on a big game hunt in Montana or South Dakota. This vast and somewhat untamed part of our country holds amazing beauty. My dream would be to set out on a week- long, horse-guided hunt with my dad and four brothers into the high country for elk or mule deer.

CC How satisfying has it been to be a doctor – both while deployed and now as the director of Summit Health in Thousand Oaks?

DW I love being a doctor. The life suits me well. My book tells stories of hardships and challenges that tested my will, but the truth is I sought out an adventurous life, and it sought me right back. My journey took me where I was meant to be and molded me into the physician, husband and father I am today. The skills I learned and refined as a military doctor gave me the foundation I needed to successfully start and grow a private medical practice in an incredibly challenging environment.

I love sharing my history with my patients – especially the veterans under my care. I am also proud to employ two for- mer military members and am always looking to hire more!

CC What do you hope people take away from reading your book?

DW The first takeaway is that everyone has a unique story worthy of telling. My story is one of many passed down by the grace of God, and I feel fortunate to share it. Untangling the mystery of life is the ultimate adventure. Finding peace on that journey is the ultimate challenge.

At the end of my journey, I have a treasure chest to share, and I have a sem- inal message. Don’t wait for your life to come to you. With the right training, you can do great things. Among them, these three key elements: Get your heart and mind balanced, get your body fit, grab a fist full of courage, and go after it!

You are the most important person you will ever meet – don’t be late to the meeting. Take calculated chances, but expect things to go wrong and that you will make mistakes. These are not failures, rather opportunities for improvement. Learn to forgive and love yourself first, then you are ready to be a light to the world. -CC