From The Urban Jungle Of L.A. To The Alaskan Wilderness

The following appears in the October issue of California Sportsman:

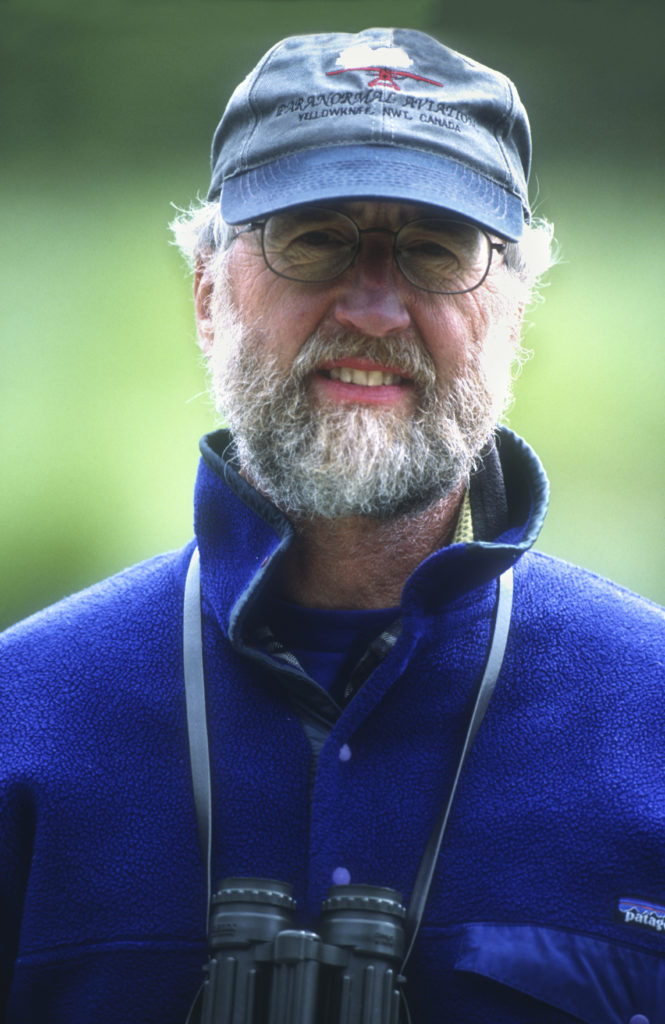

“I’d pined for a home like this my entire youth, visions of a life lived close to nature and wildlife,” author Tom Walker writes in his new book about, as part of its title suggests, “A Photographer’s Life in Alaska.” Walker grew up in Los Angeles, and in his urban youth some of his best days were spent trout fishing with his dad in the Eastern Sierra Nevada Range. Having lived more than half a century living adjacent to Denali National Park, Walker found a connection with the Last Frontier’s fauna he’s captured with a camera over years of interactions with everything from bears to salmon.

The following is excerpted with permission from Wild Shots: A Photographer’s Life in Alaska (Mountaineers Books, September 2019) by Tom Walker. This excerpt has been edited for length.

By Tom Walker

Once, I dreamed of a life at sea, on a sailboat or an island, wearing little or nothing at all. I had visions of crystal water, endless sunshine, lush ports of call and Polynesian beauties, fantasy nights cooled by tropical breezes. Memories of these teenage dreams always bring to mind one question: How the hell did I end up spending more than 50 years in Alaska?

I grew up in Los Angeles, smothered by smog, assaulted by heat and ceaseless traffic. The one great wilderness known to me as a boy, the sea, stretched west to far horizons, with distant sails hinting at mystery and adventure.

Reading The Sea-Wolf, Coming of Age in Samoa, and Mutiny on the Bounty fired my desire to be somewhere with pristine air and water and unspoiled environment. Places where wildlife – whales, porpoises, sea turtles, and albatrosses – flourished and a person could forage for food from sea and shore. Places where living meant more than a nine-to-five grind. Seeking cool offshore winds, I explored coastal tide pools and watched pastel sunsets, lured by the siren’s song of the distant unknown.

The urban landscape, the tracts of identical houses, the importance placed on glitzy cars and fashion repelled me, a child raised by parents who’d passed on their simple Midwestern values. My grandfather was an alcoholic, a mean drunk, who took his son, my father, out of the third grade to work in a coal mine. They migrated to California in the 1920s building boom to cash in on the need for labor.

My mother was 40 when I was born in 1945, my father 43, a construction worker, and neither had the inclination to guide me through the shoals of adolescence. We were poor, limited by my father’s education, living on the edge of an affluent suburb that was home to Hollywood stars like John Wayne.

Unable to blend in with others my age, who mostly enjoyed material advantages, I sought escape in wandering along the coast and among the chaparral hillsides. Studying the journals of Lewis and Clark, I became convinced I had been born in the wrong century.

EACH SUMMER MY FAMILY went camping at Mammoth Lakes in the Eastern High Sierra. Trout fishing was my dad’s cherished pastime. Twice a year, beginning when I was 2 years old, my father, mother, older brother and I made the long drive north on Highway 395 to campgrounds in the Sierra. When old enough, I dutifully flogged the water of lakes and streams, mostly without luck, all the while my eyes fixed on the distant granite spires, longing to know what stretched beyond.

Closer to home, the Santa Monica Mountains, which we simply called “the hills,” separated Los Angeles proper from the San Fernando Valley. Alone, or with [friend] Jim [Voges], I explored the rocky drainages and chaparral thickets, finding caves, a few adobe ruins of unknown origin, and one or two oases of springwater that attracted all sorts of wildlife. Today the area is part of a national recreation area, but then it was largely unprotected and threatened by development.

My first few encounters with coyotes and deer in the hills left indelible impressions – each sighting a moment of excitement in an otherwise sterile urban setting. More than one neighbor warned me that the hills were “rattlesnake infested” and to stay out. A popular horror story at that time was about a toddler bitten six times as she lifted a rattler into the air while yelling, “Look, Dad, what I found.”

With each telling the number of strikes increased, eventually to 12. By then, I had spent innumerable hours in the hills looking or snakes, trying to capture them, rarely with luck. Jim caught several Pacific rattlesnakes, which he brought home and kept in an aquarium in his room – including one specimen measuring 5½ feet – then, the biggest on record. Most of the time our snake-catching expeditions came up empty, except for loads of blood-sucking ticks.

A surprising variety of wildlife abounded in the chaparral: gray foxes, mule deer, raccoons, striped and spotted skunks, bobcats, badgers, and lots of coyotes. California quail, horned owls, phainopepla, turkey vultures, red-tailed hawks, and kestrels were common bird species. Most people living in tract homes near the edge of the chaparral had heard the yodeling of coyotes or had a deer or snake wander out of the brush and into their yards. Those animals were just a hint of what lived nearby.

Other, rarer critters lived there too, including ringtail cats and possums. In the summer of 1961, Jim captured a coati mundi, an animal far from its native range, and brought it home in a cage before releasing it a few days later. Twice we came upon the huge pugmarks of a mountain lion pressed into the canyon sand, one touch hot enough to burn the imagination. But we never saw one.

Just to the north of the valley, in the Sespe Wilderness, I saw some of the last truly wild California condors. Once while hiking I rounded a bend in the trail and surprised a condor feeding on a deer carcass. Its wingtip seemed to graze me in its panicked escape … and such a wingspan, almost 10 feet!

In junior college, I gave a presentation on the desperate efforts to save the last California condors, and was stunned when a student expressed a fear of such a “giant ugly bird” and two others muttered, “Who cares?” The comments saddened me, and I learned that most people held little concern for wildlife. (With certain extinction facing the species, in 1987, scientists captured the last 27 remaining condors for a controversial captive breeding program. Today over 500 condors fly free in Arizona, Utah, California and Baja.)

In one remote canyon in the hills, a friend and I found a sandstone cave, 20 feet high at the mouth and tapering into darkness, but the dry buzz of a rattlesnake echoing from the shadows sent us packing. The next day we returned with flashlights, a gunnysack and a crude snake stick. Searching to the narrow back of the cave, we saw only tracks and trails in the sand, no snakes or mammals.

Halfway in, our lights fell on short, deep, parallel grooves cut into the wall, some over seven feet off the ground. My friend said they looked identical to the scratchings of a bear that he’d seen on a tree in Yosemite. My splayed fingers barely spanned the scrapes. “Too big for a black bear,” my friend said. In the dim light we stared wide-eyed, both thinking, grizzly.

GRIZZLY BEARS HAD BEEN extinct in California since 1924, but we believed we’d found a relic of the past. We’d learned in school that grizzlies were once common, and the state flag predated statehood for the golden bear republic. Early vaqueros, we were told, roped bears for sport and staged fights between bears and bulls. Like elsewhere, the great bear fell to westward expansion, gone the way of the wolf. I still cling to the notion that we found the claw marks of a grizzly in that cave.

Grizzlies and wolves seemed to be lost treasures of North America’s marvelous megafauna and gone for good from California. In a stunning turn, in 2011, a radio-collared wolf – designated OR-7, nicknamed “Journey” – wandered into Northern California after an epic 1,000-mile trek, the first of its kind since 1924.

The Yellowstone wolf recovery project had succeeded beyond any expectations, with the canids spreading across the west. OR-7’s arrival in California was greeted with the mix of delight and loathing that the species provokes everywhere. In 2015, researchers released photos of the Shasta Pack, the first wolf family group in California in a century.

No one believed me when I described the things I saw in my wanderings. My interest in photography was born of a need for evidence – as proof of the bucks I stalked, the snakes we caught, and the raccoons that peered down at us from live oaks. Whenever I got the usual “Right. Sure thing, kid,” I’d pull out a stack of prints and point. It would be years before I could afford a good camera, but even those grainy snapshots were invaluable treasures.

FROM MY SCIENCE TEACHERS and my own readings, I had formed a clear image of early California. Two hundred years ago Southern California was a compelling natural landscape, home to wildlife as diverse as elephant seals and grizzly bears. You could look one way at snowcapped peaks, look the opposite way and see surf pounding rocky coastlines, where the warm desert winds were cooled by sea breezes. With a temperate, almost Mediterranean climate, the soil, when irrigated, would grow just about anything – cotton to cantaloupes.

As I was growing up in the 1950s and early ’60s, the building boom that had begun in the 1920s was roaring full tilt. Bulldozers turned chaparral-covered hillsides into terraces for tract homes, developing a sprawling metropolis of concrete, steel, and asphalt spiderwebbed with new freeways.

In the era before the federal mandates of the Clean Air Act of 1970, smog often rendered the summer air unfit to breathe. The ugly brown haze seared our eyes and lungs. With the temperature frequently above 90 degrees, summer conditions were usually intolerable, the only escape the beach or the distant Sierra. The frequency of bulldozers knocking over live oaks and manzanita, scraping the land flat and bare, disgusted me. There seemed to be no hope for the natural landscape that I had fallen in love with.

On my last visit to LA, in the wake of my mother’s death, in need of solitude and an escape from grief, I drove into the hills to my most treasured sanctuary, a perennial stream we called Stunt Creek. Fearful of what I’d find, I almost didn’t go. In high school I’d spent hours on the creek looking for owls and quail, lizards, king snakes, and salamanders, the summer heat cooled and freshened by the dense vegetation.

Turning onto Cold Creek Road, my heart fell, my worst nightmare confirmed. Terraces of California ranch-style houses, with typical red-tile roofs, crept up the hillside – the chaparral, sumac, chamise, and scrub oaks bulldozed away. I slowed almost to a crawl as I rounded the last bends to where the creek crossed the narrow road.

Negotiating the last curve, I was confounded – the slopes on both sides of the drainage were untouched, dense chaparral and live oaks choking the lower riparian zone. I parked in a pullout opposite a padlocked chain-link fence that spanned the canyon mouth. The sign on the gate, across our old foot trail, read:

NO TRESPASSING

MANAGED BY THE SANTA MONICA MOUNTAINS CONSERVANCY. THIS PROPERTY PROTECTS THE COLD CREEK WATERSHED, PERHAPS THE BEST PRESERVED AND MOST BIOLOGICALLY DIVERSE WATERSHED AREA WITHIN THE SANTA MONICA MOUNTAINS.

Out of relief that this treasure had been spared, on top of my grief from my mother’s death, I cried. CS

Editor’s note: For more on Tom Walker’s book Wild Shots: A Photographer’s Life in Alaska and how to order a copy, go to mountaineers.org/books/books/

Q&A WITH AUTHOR TOM WALKER

California Sportsman editor Chris Cocoles caught up with Wild Shots author and photographer Tom Walker to learn more about his California roots, love of wildlife photography and experiences in Alaska.

Chris Cocoles Congratulations on this latest book. It’s fantastic. Was Wild Shots maybe more sentimental for you than some of your previous work?

Tom Walker I would not say sentimental at all. Maybe reflective would be a better term. At this point in my life, my goal was to record what I think were some fairly unique incidents and insights. Previous works have been how-to, biographies and natural histories, with this work in the latter category.

CC You’ve been in Alaska for 50 years now. What was your early experience like in the Last Frontier?

TW Fifty-four years now. In a word, the experience was invigorating. With so much new and so much of intense interest, I could not soak it all in. Wishing for a few years, I had a must-do list of places to see and experience. The list is longer today.

CC I’m pretty envious of you that Denali National Park is almost your backyard. What’s that been like for you?

TW Heartbreaking. To love some terrain so much and see it change so much in a negative way, it has been difficult. Climate change is very real and to watch the effects on the wildlife and plants that have evolved over millennia is difficult. Here in the Far North, the concept is not abstract but a real ongoing process that people who look to nature can readily see and experience.

CC Tell me about growing up around Los Angeles and how the outdoors shaped your life.

TW The outdoors was salvation. I think some people are just cast into places they are not geared for or supposed to be. At heart I was a country boy and living in the city was for me the proverbial square peg. Once I could wander freely into undeveloped spaces, deserts, shores, and mountains, did I find a measure of peace.

CC You write about your dad’s love of trout fishing and the trips you took in your California days. Can you share a memory of fishing with your dad?

TW Hiking to an alpine lake with my dad, just he and I, to fish for golden trout was a memorable trip complete with a close look at two big mule deer bucks. Fishing a shoreline of a crystalline lake with no one else around was a peerless memory.

CC What’s the biggest challenge about photographing wildlife?

TW Not drowning, dying of hypothermia, falling off a cliff, or crashing in a small plane. The wildlife, if you have studied your critters, poses the least risk. Alaska – and it’s true of northern Canada as well – is difficult country with challenges of weather and remoteness.

CC Do you have a favorite species of animal that you’ve really savored interacting with and taking photos of?

TW Dall sheep. I love the high mountains where they live, the vista they savor every day, and their ability to thrive in such inhospitable (to humans) terrain. Imagine living where the wind shrieks, the thermometer drops to minus 60 or more, and the night can be 24 hours long in winter. They are tough but gorgeous creatures.

CC What has been your fishing experience like since moving to Alaska?

TW Mostly salmon in both saltwater and fresh. Silver salmon and red salmon offer great freshwater fishing. The best sportfishing has been for sheefish, the so-called “tarpon of the north,” which are great fighters and wonderful eating. It may be my weird thinking, but I never fish for king salmon. I worked on a rehab project for this species and don’t want to kill one.

CC You have a chapter about polarizing grizzly bear personality Timothy Treadwell and the relationship you had with him. Can you sum up what his legacy will be?

TW He did more harm than good. He had a true gift in reaching out to children and giving a conservation lesson. But in the end, when he died it was all undone.

CC Obviously, hunting is such a huge part of the fabric of Alaskans. What’s your take on hunting in the state and how it can be better or more effective in terms of conservation?

TW All I will say on this topic is Alaskan wildlife resources are finite and there will never be enough to meet the demand. Overharvest has been a problem in the past and as the population grows, careful management will be needed to guard against future depletions.

CC In terms of climate change, California suffered through an extended drought and though the state did see a huge improvement of rainfall in the last couple years, so many wildfires and mudslides have affected communities seemingly everywhere in the state. What will it take to convince more skeptics that climate change is a legitimate concern?

TW Can’t really answer that, except to say the issue is so political that some people will never see the light until Des Moines is a coastal city.

CC Salmon in both Alaska and California are under siege for various reasons. Do you have a hunch on what might happen to these remarkable fish in the future?

TW Again, beyond my expertise. (But) here (in Alaska) we have a proposed Pebble Mine that will threaten the greatest wild salmon runs in the world. Imaging risking a pristine food source that feeds thousands, if not tens of thousands of people, for copper. Crazy.

CC You’ve seen a lot in the wilderness in your time exploring. Is there something you haven’t seen that you hope to accomplish someday?

TW Anything to do with wolverines. I have seen about a dozen but would like a closer, longer observation. It’s perhaps our least understood critter.

CS You also touched on the extinction of grizzly bears in California and also about the wolves that have found their way into Northern California. As a conservationist, is it kind of bittersweet and ironic now that the grizzly bear is literally a symbol for California but nowhere to be found?

TW Very much so. Perhaps it is pie in the sky to believe a potentially dangerous animal can coexist in an area so densely populated, but education is the key along with a forbearance by the public. Bears have proven to be way more tolerant of people than vice versa. CS